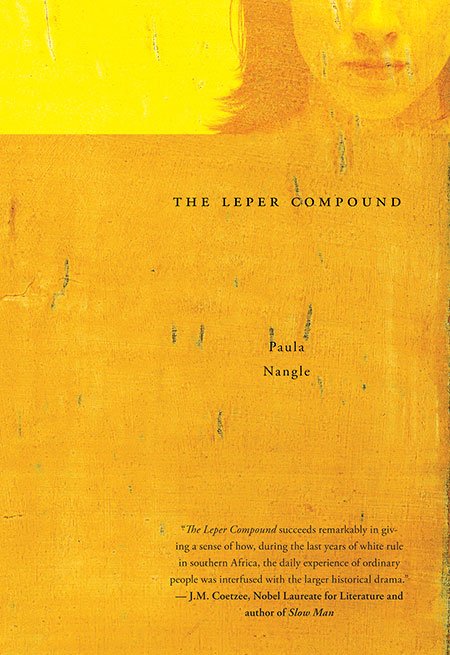

“The Leper Compound will … remain with the reader long after the book has been closed.”

Stuart Dybek, author of I Sailed with Magellan

-

on

“The Leper Compound interweaves the study of a historic moment with a lovely depiction of one African girl’s development as affected by that moment.”

San Francisco Chronicle

( link)-

on

“The Leper Compound succeeds remarkably in giving a sense of how, during the last years of white rule in southern Africa, the daily experience of ordinary people was interfused with the larger historical drama.”

J.M. Coetzee, Nobel Laureate for Literature and author of Slow Man

-

on

“Nangle looks at the suffering body with a concentration that yields almost hallucinatory detail. What she writes is a stunning realism like no one else’s, explosively quiet, painful, and beautiful.”

Jaimy Gordon, author of Bogeywoman

-

on

For Colleen, motherless at seven, isolated from her schizophrenic younger sister, illness unleashes the uncanny and essential of human identity. Growing into womanhood in Rhodesia’s final conflict-ridden years, she transgresses social, racial, and political boundaries in her search for connection. This masterly novel is a searing evocation of late-twentieth-century African life.

A Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers selection

Excerpt from The Leper Compound

Penny spotted the anopheles mosquito one mid-morning break at Hatfield Girls’ High School. Most of form 2A lined the upper balcony, sitting on the sun-warmed concrete with bags of potato crisps, vigilant of prefects, their pleated uniforms bunched at their thighs for prime tanning. They shaded their eyes as Penny pointed. Then everyone saw the mosquito on the white railing, its pointed bill aligned with its body. There was a pause before they charged the form room. They blinked in the sudden, cool dark, breathless, uttering various bits of Afrikaans slang.

The anopheles was rampant this year, Miss Dunn said in biology. “I hope you’ve all been taking your quinine, girls.” Colleen’s face felt hot with guilt. She wondered if protozoa spun up and down her body in the flow of blood, drinking iron, bursting their way through valves. They would divide into numbers too long for a calculator. She played with her pencil, making it wobbly and buoyant. She had seen Ministry of Health movies about teen pregnancy. A girl, an actress, rubbed her temples and shook her head with secret knowledge. “I’m pregnant,” the girl finally said to her mother.

“I forgot to take my quinine,” Colleen told the boarding mistress, and gave her the aluminum packet. It was moist and crinkled from the sweat of her palm. The woman held it before Colleen’s face, its intact green pills in horizontal rows, something to read from left to right and understand completely.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Long after Colleen grew up, her father still talked about the malaria. “You weren’t even there,” he would say. “Mostly you were gone, you didn’t even see me. I thought you were dead.” He would repeat himself, marveling, she supposes, that she didn’t die like her mother, one morning years ago, of an unknown fever. Colleen had thought she was asleep, curled up on her side with the tea tray steaming next to the bed. The parquet floor was cold through the rubber feet of her pajamas. Her mother had not been dead long, they said, because when Colleen had climbed in next to her, she was only limp, only sleeping, her hands cool, not hot like the night before, and Colleen rested her head against her mother’s warm chest. After a while, she noticed how her head did not rise up and down the way it usually did—a kind of ride, since at seven she could no longer be rocked—and she wondered if her mother was teasing her, holding her breath, and Colleen held her breath too, and no one moved, nothing, not even their eyes.

Malaria must have seemed more definite to her father, an infection with a household name, perhaps a thing he could stop with his knowledge of its seriousness. He flew up to Salisbury in a single-engine Cessna. He stayed on the sixth floor of the Monomatapa Hotel, as if he were on holiday. Colleen remembers chills, and the infusion of chloroquine, lukewarm with the burn of ice. The hospital had been the dark gray of a back stage, an outer world. Her hand seemed used to flapping in the air. It had tried to catch mammals with peacock-feathered wings, reached to touch soft, wrinkled faces with sad eyes. Sometimes the faces would leer. “Go away,” she would say, or “Fuck you,” and her father’s chair would scrape across the floor in a surprised way.

“Open your eyes, Colleen.” Her father had tilted her distracted chin toward him. “You’re in hospital.” He spoke to her as if she had lost her hearing. His mouth stretched his face. His skin was dry and transparent from the sun and reminded her of Mapipi’s phyllo pastry. “Do you know where you are? Rhodesia.” The loud sounds pierced her head. “Colleen, what day is it today? Monday.” She dreamed of surprise quizzes at school. She felt unprepared.