“[Green’s] prose rings with the elemental clarity of the ice he knows so well.”

PEN Awards Committee citation

-

on

“Nature writing of a very high order. . . . A joyride for those who enjoy deep explorations of logic, human frailty and the laws of nature.”

San Francisco Chronicle

( link)-

on

“Brilliant. . . . Resembles at various times the work of Stephen Jay Gould, Loren Eiseley and Barry Lopez, but also Primo Levi’s The Periodic Table and the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins and the writer of Ecclesiastes. It’s the kind of book that makes the reviewer want to quote whole paragraphs.”

Plain Dealer

-

on

“Among his many accomplishments, [Green] offhandedly makes the vocabulary of science accessible to the lay reader. He is at ease in the kingdom of poetry—just as much as he is (warily) at ease in the frozen and eerily beautiful Antarctic landscape.”

Boston Globe

-

on

“Some of the prettiest prose ever devoted to the subject of water and lakes and rivers, clouds and rain and fog. A beautiful little book; it will go on the shelf with the other books I read for the love of their words.”

Houston Chronicle

-

on

“A lucid, wondrous account. . . . This authoritative yet lyrical book blends science with art in the enthusiasm that Green feels at being the creator of a new understanding where none was before.”

Winston-Salem Journal

-

on

“Compelling. . . . This book is not only filled with wonder, but also hope.”

Cincinnati Post

-

on

“A magical work of meditation and precise science.”

ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment

-

on

“Poetic and passionate. . . . Green affirms the fact that science, like art, is rooted in pure imagination.”

Booklist (starred review)

( link)-

on

“Wonderful. . . . In evocative language, Green successfully moves between arresting natural history and sophisticated but accessible philosophy of science. . . . With gripping accounts of a number of near death experiences added to the mix, the whole is a thoroughly enjoyable and remarkably informative exposition of the life of a field scientist.”

Publishers Weekly

( link)-

on

“Finely honed flashes of pure scientific writing.”

Kirkus Reviews

-

on

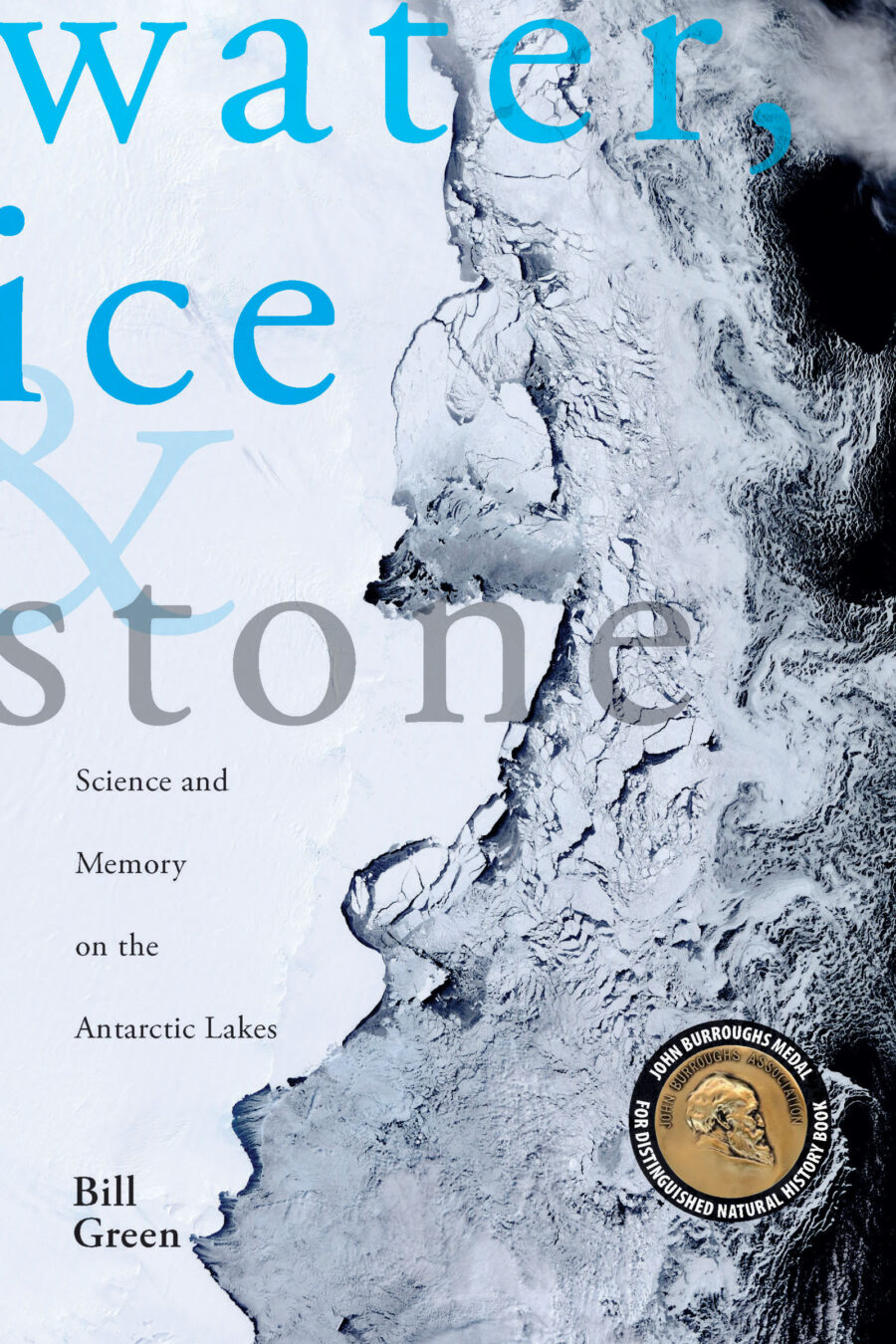

A classic of contemporary nature writing, the award-winning Water, Ice & Stone is both a scientific and poetic journey into Antarctica, addressing the ecological importance of the continent within the context of climate change. Bill Green has been traveling to this remote and primordial place at the bottom of the Earth since 1968. With this book he focuses on the McMurdo Dry Valleys—an area that is deceptively timeless as a stark landscape of rock and ice. Here, Green delves into the geochemistry of the region and discovers a wealth of data, which vividly speaks to the health and climate of the larger world.

John Burroughs Medal for Distinguished Natural History Book

PEN/Martha Albrand Award Finalist

Excerpt from Water, Ice & Stone

I first went to Antarctica in August of 1968 as a member of a research team led by Dr. Robert Benoit of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. Benoit had been awarded a grant by the National Science Foundation to study the microbiology of a strange group of permanently ice-covered lakes located in the rugged coastal valleys (now called the McMurdo Dry Valleys) near the Ross Sea. The lakes had been discovered by the first expedition of the great Antarctic explorer Robert Falcon Scott (1901-4), but only a few scientists had visited them in the intervening years and little had been written about them in the scientific literature. In 1968, I was a graduate student at work on a project in physical chemistry and nearly a year away from completing my doctoral program. When I heard that Benoit and his graduate assistant, Roger Hatcher, needed a chemist, I quickly volunteered, thinking that this would be a wonderful way to learn some- thing about limnology, the science of lakes, and to explore a part of the world that I would most likely never see again.

From the outset, I found the science, and indeed, everything about the Antarctic continent, fascinating. It was the most austere and beautiful land I had ever seen, and I was drawn to it immediately, in ways and for reasons I did not understand. When I was not analyzing the unimaginably clear waters of Lake Vanda or Lake Bonney, two of the ice-covered lakes we had come to study, I was walking and thinking and writing page after page of notes in my journal, trying to describe what I was seeing and feeling in this improbable Eden of ice and stone. My words seemed always to fall short, and seem to do so to this day.

The years passed after that first encounter, but the lakes and the valleys of Antarctica remained vivid memories, a daydream away. Gradually my professional interests turned from the pure laboratory chemistry in which I had been trained to the science of geochemistry. From the courses that I was teaching and from the Midwestern lakes that I was studying, new questions began to arise. I began to think that the answers might lie in the distant waters of the Dry Valleys that I had once visited with Hatcher and Benoit.

In 1980 the National Science Foundation funded my proposal to study the behavior of nutrients (compounds of nitrogen and phosphorus that control the biological productivity of a lake) and heavy metals (elements such as manganese, iron, cobalt, nickel, cadmium, and lead) in Lake Vanda and its inflow, the Onyx River. This turned out to be the beginning of a ten-year investigation that gradually encompassed more lakes and more subtle and vexing questions. How and when had these odd water bodies evolved? Why were they so different in their chemical compositions? How were they sustained biologically in such a harsh environment? How were the chemical elements transported to them, and how were those elements removed? Because they were so biologically uncomplex, might these lakes not serve as beautifully simple models for other bodies of water on the Earth? Perhaps even the oceans? Because they seemed to cleanse themselves of the metals brought into their waters, might they not tell us something about the way the Earth regenerates itself? These were some of the questions that brought me back to Antarctica five more times during the 1980s and, most recently, from October to December of 1994.

Thus the present book draws on more than fourteen months of journal notes collected over seven field seasons. It arose, I think, from the need to talk about the Antarctic work in a more reflective and personal way—in a way that could not easily be accommodated within the pages of professional journals. From the outset, the continent raised questions for me that went beyond the purview of science. These were questions about the ways we experience the world and respond to its physical settings; how we decide, as individuals, to do with our lives what we do with them; the sources of our wonder; the nature of science itself. If the book appears to have a spiritual dimension, that seems only fitting, given the place in which it was written. For Antarctica is the most sublime of continents, a land of light and darkness, of scrawls and traces and hints of eternity.