In this thoroughly entertaining science history, Switek combines a deep knowledge of the fossil record with a Holmesian compulsion to investigate the myriad ways evolutionary discoveries have been made…It’s poetry, serendipity, and smart entertainment because Switek has found the sweet spot between academic treatise and pop culture, a literary locale that is a godsend to armchair explorers everywhere.

— Booklist

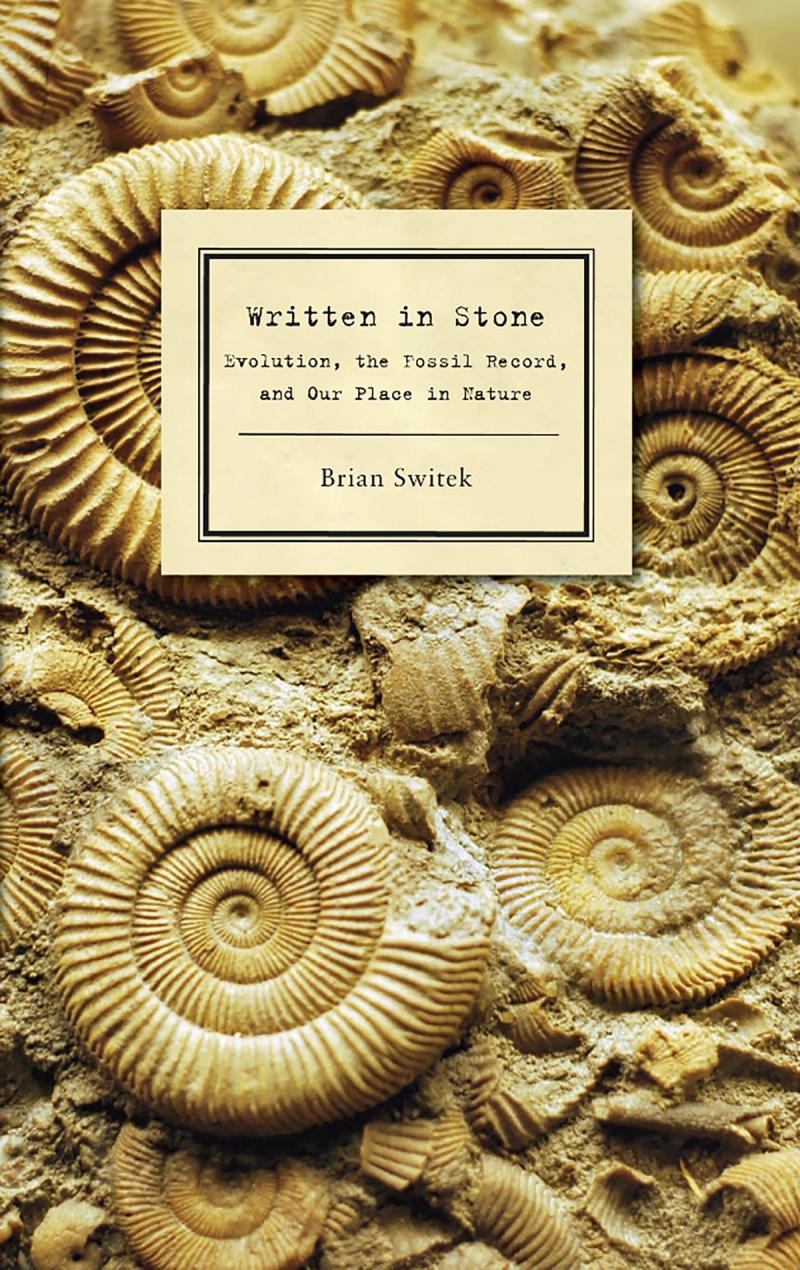

Written in Stone

Evolution, the Fossil Record, and Our Place in Nature

When Charles Darwin unveiled his revolutionary idea that life had evolved by means of natural selection it made sense of the whole of biology, yet it was dogged by a major problem: the transitional fossils that would confirm Darwin’s predictions were seemingly nowhere to be found. The absence of these “missing links” became one of the most hotly debated issues in evolutionary science.

Only now—through advances in paleontology, molecular biology, and genetics—can the comprehensive story be told. Written in Stone is the first popular account of the remarkable discovery of these fossils (from walking whales to feathered dinosaurs and hominins of all types), the debates they engender, and how today’s discoveries have changed our perspective of the tree of life. By combining the most up-to-date scientific research with the history of science, Written in Stone explores our changing ideas about our place in nature and celebrates the remarkable variety of life on Earth.

Ebook

- ISBN

- 9781934137369

Paperback

- ISBN

- 9781934137291

Brian Switek is a science writer and amateur paleontologist whose books include Written in Stone: Evolution, the Fossil Record and Our Place in Nature, which was named a Choice Outstanding Academic Title of the Year, My Beloved Brontosaurus, and Prehistoric Predators. In addition to his acclaimed blog, Laelaps, he also writes about fossils and natural history for publications such as the Wall Street Journal, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Nature, Scientific American, and Slate. He lives in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Praise for Written in Stone

In Written in Stone, Brian Switek simultaneously depicts our place in Nature while capturing the flavor of discovery and understanding our remote past in the fossil record. Elegantly and engagingly crafted, Switek’s narrative interweaves stories and characters not often encountered in books on paleontology—at once a unique, informative and entertaining read.

— Niles Eldredge, author of Darwin: Discovering the Tree of Life

Brian Switek’s Written in Stone is a wonderful journey through the fossil record, and the people and events that have shaped our understanding of fossils and their meaning. He weaves in entertaining anecdotes about the scientists and their discoveries (impeccably researched and up-to-date in historical detail) with our current view of these creatures, utilizing all the latest discoveries from new fossils to molecular biology. After reading this book, you will have a totally new context in which to interpret the evolutionary history of amphibians, mammals, whales, elephants, horses, and especially humans.

— Donald R. Prothero, author of Evolution: What the Fossils Say and Why it Matters

It is hard not to be awed reading Brian Switek’s magisterial Written in Stone. Part historical account, part scientific detective story, the book is a reflection on how we have come to know and understand ancient events in the planet’s history. Switek’s elegant prose and thoughtful scholarship will change the way you see life on our planet. This book marks the debut of an important new voice.

— Neil Shubin, Professor and author of Your Inner Fish

Brian Switek proves himself a compelling historian of science with Written In Stone. His accounts of dinosaurs, birds, whales, and our own primate ancestors are not just fascinating for their rich historical detail, but also for their up-to-date reporting on paleontology’s latest discoveries about how life evolved.

— Carl Zimmer, author of At the Water's Edge and The Tangled Bank: An Introduction to Evolution

If you want to read one book to get up to speed on evolution, read Written in Stone. Switek’s clear and compelling book is full of fascinating stories about how scientists have read the fossil record to trace the evolution of life on Earth. In it, you will read how dinosaurs gave rise to birds, how small deer-like land animals evolved into whales, and how many types of horses, elephants and early humans once roamed the Earth. In short, you will see how scientists through the ages have figured out man’s place in nature.

— Ann Gibbons, author of The First Human