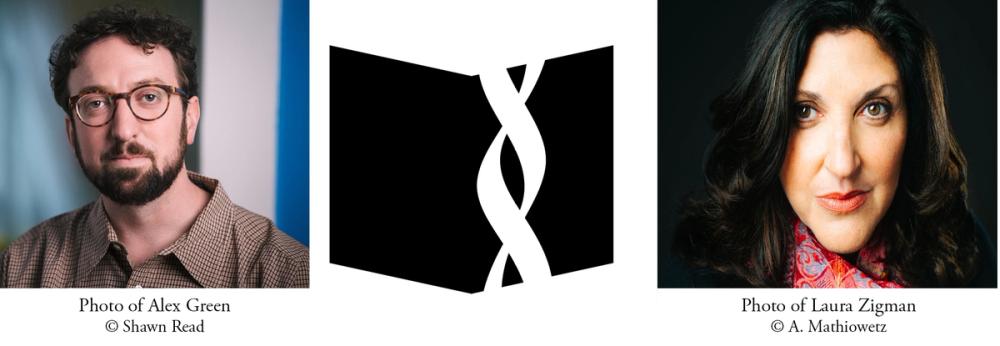

BLP Conversations: Alex Green and Laura Zigman

In this conversation, Alex Green, member of the faculty at Harvard Kennedy School and author of A Perfect Turmoil: Walter E. Fernald and the Struggle to Care for America’s Disabled, and Laura Zigman, author of Small World, discuss their shared connections to the Walter E. Fernald State School, the large-scale institution at the heart of both their books. This conversation is part of the BLP Conversations series from Bellevue Literary Press, featuring dialogues that explore the creative territory at the intersection of the arts and sciences.

Alex Green: Your novel, Small World, is fictional, but much of it is based on your own experience of having a disabled sister who passed away at a young age in the massive institution that was named for the man I’ve written about in A Perfect Turmoil. These are stories enveloped in decades-long silences. When you set out to begin writing the book, what worried you most about raising up such a deeply personal story from your past, looking at it as an adult, and trying to put it into words?

Laura Zigman: I think what worried me most about telling that story—the story I’d waited my whole life to write about—had to do with current fears around language and around the concerns about who gets to tell what story. I was three when my sister Sheryl died while at Fernald, and for years afterwards my parents remained involved with the parents’ advocacy group that raised money and awareness for the institution and for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Every year there was a fundraising dinner dance, and a month before that my parents would send my older sister Linda and me out into our neighborhood with books of raffle tickets to sell. Our sales pitch? Would you like to buy a ticket to support retarded children? That was the word we used in the late 1960s and early 1970s—that word and other words that we don’t use now. I had to use them in the flashback scenes in the book because those words were used then, and it’s important to be honest about that and not whitewash how things were.

Luckily the sensitivity reader that my publisher hired understood my usage and didn’t flag it, but I worried that readers would take offense at it anyway, despite the context. I was also concerned about whether other parts of the story would somehow be offensive to families with children with disabilities, and I was tempted to show a few friends the manuscript to see if they had any issues with it, but I came to understand that I wasn’t writing a parent’s story. I was writing a sibling’s story, my story, of what it felt like to grow up the way I did, and that I was entitled to tell that story. That said, my British publisher would not publish the novel—she found it incredibly offensive, apparently, because it sounded to her like I was saying that having a disabled child is a burden. Which it is—it’s incredibly hard, it’s incredibly difficult, financially and physically and emotionally, and to say it isn’t is a lie—but it’s a burden parents carry with love and joy, too.

You begin A Perfect Turmoil with a note about the much older words we have used when we talk about disability and your choice to leave them in place for the book, even though they’re incredibly hard to hear and read. How did you arrive at that decision?

AG: You’re right, the book is filled with frankly horrible-sounding words, and I wouldn’t discount how much that relates to the fact that so much of this history is untold. I think that many scholars have probably encountered the edges of this history, and when they read words like idiot, imbecile, moron, and feeble-minded, they read them from a modern context and backed away. I’m certain that this is why some of the history written about these ideas is not as nuanced as it could be. But those terms were used in fascinating, important ways that related to how we saw and treated disabled people. For instance, when Walter Fernald uses the term imbecile at the beginning or end of his career, he means it in a diagnostic way, as a medical term. He also often means it with compassion and love for the disabled person he is writing about. But when he says imbecile from about 1900 to 1915, he means the very thing that one of his papers is titled, “The imbecile with criminal instincts.”

There’s a throughline from that word at its worst to a new category of disability Fernald thought he’d identified called “defective delinquency,” which meant that a person’s disability was expressed as delinquency. And there’s a direct line from that term to the one Henry Goddard invents to describe the very same kind of disability around 1910: moron. The challenge is to see the context in which people were using these words to get clues about their intent, but the problem is that these terms have no synonyms today. For instance, the idea of the moron is entirely based on the Goddard’s creation and use of the American version of the IQ test on a captive population of disabled people living in an institution similar to Fernald’s. The problem is that ideas about intelligence and its measurability that make the foundation of the IQ were (and are) bogus, so his “discovery” of the moron isn’t real. It’s just bad science.

You mentioned selling raffle tickets to support the school, which could seem like a bake sale, but was actually part of the beginning of a major civil rights push that became the deinstitutionalization movement. At the same time, in the novel, you note the kind of silencing shame these places had on people like your mother. How can we hold both truths of this in our minds at the same time: that people knew about these places and knew that conditions were terrible in them, and at the same time, we didn’t talk about them?

LZ: I think the answer to this difficult question comes down to two words: shame and judgment. Shame is heaped on parents of disabled children because, deep down, there has always been discomfort with difference of any kind, especially disability—and especially when it comes to parents comparing their children with other children—and judgment because there’s always the silent question of what a woman may have done wrong during her pregnancy to “cause” the disability, or what defects were lurking in the parents’ genetics. It’s a double header, this shame/judgment combo. Parents of disabled children feel the sting of the milestones and norms their child will likely never achieve physically and/or intellectually and have to metabolize their own sadness around that and the shift in their expectations. Parents of “healthy” children often feel an array of complicated feelings that include generalized discomfort around children with special/different needs for fear of not knowing what to say or how to act around them. Often they exude a kind of there-but-for-the-grace-of-God-go-us relief that is palpable to parents with disabled children.

Children are mirrors—we see ourselves in them, or want to—our expectations for achievement and beauty and success and failure in all ways are tangled up in the very public act of childhood. Again, most people are just not comfortable around disability. I remember when our son was young, we were friends with a family who had a son with cerebral palsy, and the mother told us how often other mothers asked for playdates with her son “because it would be good for their kids” to be around him. She never got over the shock of how they said the quiet part out loud—the horror of feeling like her son was being used as a “teaching moment” for other people’s “healthy” children. When it came to the question of institutionalization and deinstitutionalization, there was a similar elastic band of shame and judgment being pulled and released: Yes, we should support advocacy for the civil rights of the disabled so that they can get out of these awful institutions, but sorry, we really don’t know what to do with them once they’re no longer hidden away inside those awful places. There were no solutions, and no true understanding of the needs of families for long-term care of special-needs children who would later become young adults and grown adults who would live into middle age. It’s part of that long-standing sense that disability is otherness, and otherness and diversity have, sadly, never been widely accepted and embraced concepts in this country, and so most people really don’t know how to talk about difference and how to care for those who need it most.

That’s what’s fascinating about Walter Fernald, is to see someone who was willing to talk about difference and was willing to try, fail, and try again to care for those who needed it most. What can we take from that today?

AG: There’s so much there, but one thing Fernald did very effectively stands out. When he spoke to large audiences, he often named their prejudice in terms that were non-judgmental, as a simple matter of fact. He would say, “This is how you see disabled people and I get it.” But at the best points in his career, he’d then walk them, step by step, through that prejudice to the human beings they couldn’t see on the other side of all of their preconceptions, and get to a place of caring, and a very practical place of how to do that. I think we can learn a lot from this because it’s an effective and compassionate way to move beyond the shame and silence you’re talking about, to compassion and humanity. I think the downside to it is that it does this by breaking down our prejudices into a series of problems that need to be solved, and that can be risky because it can shift, subtly and powerfully, to the idea that the disabled person is the one with a series of problems that need to be solved, which isn’t right. Disabled people are humans who deserve the same welcome as anyone else. But I think some of the rudiments are there, and we’re at a stage in this country where perhaps we need to start with rudiments.

Alex Green teaches political communications at Harvard Kennedy School and is a visiting fellow at the Harvard Law School Project on Disability and a visiting scholar at Brandeis University Lurie Institute for Disability Policy. He has piloted a nationally recognized disability history curriculum for high school students, developed and taught the first graduate disability policy course offered at the University of Massachusetts Amherst School of Public Policy, and is the author of legislation to create a first-of-its-kind, disability-led human rights commission to investigate the history of state institutions for disabled people in Massachusetts. He lives outside of Boston. A Perfect Turmoil: Walter E. Fernald and the Struggle to Care for America’s Disabled is his first book.

Laura Zigman is the author of six novels, including Small World; Separation Anxiety (which was optioned by Julianne Nicholson and the production company Wiip (Mare of Easttown) for a limited television series); Animal Husbandry (which was made into the movie Someone Like You, starring Hugh Jackman and Ashley Judd); Dating Big Bird; Her; and Piece of Work. She has ghostwritten/collaborated on several works of nonfiction, including Eddie Izzard's New York Times bestseller, Believe Me; been a contributor to the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Huffington Post; produced a popular online series of animated videos called Annoying Conversations; and was the recipient of a Yaddo residency. She lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where she helps clients via Zoom, phone, and sometimes in person with their writing. She is also at work on two new novels.