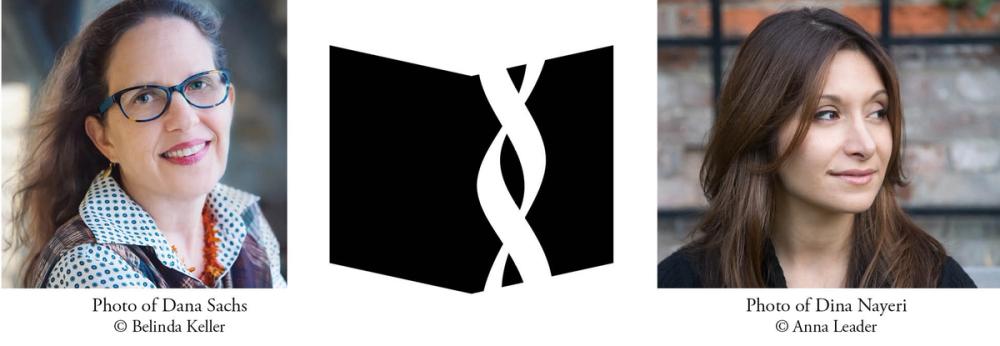

BLP Conversations: Dana Sachs and Dina Nayeri

In this conversation Dana Sachs, author of All Else Failed, and Dina Nayeri, author of Who Gets Believed?, discuss the art of individualizing the universal, the concept of good storytelling across cultures, and the benefit of finding just the right word for the story. Their conversation is part of the BLP Conversations series from Bellevue Literary Press, featuring dialogues that explore the creative territory at the intersection of the arts and sciences.

Dana Sachs: Your latest nonfiction book, Who Gets Believed?, is about belief, performance, truth, morality, and a lot of personal stuff, as well. It explores the idea of belief in different realms of experience. You tell stories about a management consultant, an asylum seeker, a torture survivor, an emergency room doctor, firefighters, and a guy named Lamar who’s jailed for a murder he didn’t commit. By picking very specific situations, you individualize the larger issues, making them very human but also universal. If you’re lucky and you’re writing well, the prose can have this magical effect of making the reader feel connected to that individual.

Dina Nayeri: When you’re first shaping the story, you think, I’m going to show that all these little arenas of belief and performance relate to each other. Whereas the point is made simply by showing the individual stories. This and the last book, The Ungrateful Refugee, started with an idea. Once you get into the story you realize that all you need to do is to show that person in that situation, let the stories resonate with one another, and then remove the scaffolding. That is a huge challenge because I am someone who likes to say what my ideas are.

DS: But in the end, these stories become our most effective tool. I recently heard from a reader who had just finished All Else Failed. He pointed to several moments in the book that he found intensely moving and all of them were stories. In one, a Syrian dad was preparing to put his family into a rubber dinghy to travel from Turkey to Greece. The man wanted to buy life jackets, but he’d heard that some were fakes—when they got wet, they’d absorb water and cause people to drown. So, the dad spent all this time on his phone, conducting research to figure out how to buy the right life jackets for his family. It broke my heart when he told me that story. I’m a parent, too, and I could imagine the panic I would feel in that situation. The story conveys the predicament in a way that a more abstract idea could never do. It’s like the “show-don’t-tell” issue in writing.

In your new book, you talk about The New Yorker short story model and subtlety. I’m thinking of Raymond Carver, whose writing doesn’t tell the reader what to think. You’re supposed to just feel it. You’ve described how that is so different from the Iranian experience, or the wailing of a person in grief.

DN: A while back, The New Yorker posted line-edited versions of “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love.”

DS: I did hear that there are questions of how much of that style was Carver, and how much of it was his editor, Gordon Lish.

DN: I think if you read the line-edited version, you see how much of it was Gordon Lish. There are all of these flaws and self-consciousness and saying too much in the Carver version. Then Gordon Lish came with his elegant brush and brushed over it. For me, it was such an interesting example of what we think in each culture is good storytelling. In Iran, melodrama isn’t a bad thing that we think it is [in the U.S.]. Showing your emotions loudly is the truth of emotions in many Middle Eastern cultures.

DS: People from cultures of power can say “this is an acceptable way of writing” or “this is over the top.” It reminds me of a personal experience I had recently. My dad died and there were a lot of us around his bed when he died. Two of these people are family members from Mexico, and at the moment when he was about to die, they started wailing. My family is Jewish, kind of more controlled, and I said they either had to leave the room or stop. I thought it was affecting my dad—it was definitely affecting me—and it was a culture clash. After he died, we had to talk about it. Wherever we come from, we can’t get away from the structure that raised us.

DN: The interesting theme in that story for me is that you are someone so aware of this, but at the moment when we’re having our own emotional reactions, it’s absolutely impossible to leave what we grew up with. The sensation of extreme discomfort is so familiar to me. I think a lot of third culture kids will talk about this. Even if you are raised in two cultures, like I have been, Iranian and American, and you are well-versed and you travel between [the two cultures], there are moments that are so raw and emotional that one of those will win, and if someone else expresses themselves in the other way then you have these visceral reactions. You realize which ones you are.

DS: Is there one that you go to more quickly or more solidly?

DN: I think it really depends on what the situation is, but I think probably more American. I’ve had so many big emotional firsts as an American, so I think if I were in your shoes, I would react very similarly. If someone was dying, and I was trying to have my reaction, I think that if a group of Iranian wailers came in, I would want them to leave.

DS: You and I write both nonfiction and fiction. People often ask me which is more challenging. I always say I am a storyteller in both forms. What about you?

DN: I think they give me very different things. I would say that we’re storytellers and we use a lot of the same tools. It matters more whether we are writing short or long than whether we are writing fiction or nonfiction. When I am writing an essay or a short story and I know I have five thousand words, then I know the swells, where I need to start moving this way or that way, whereas if I start to get into a longer book, whether it be a fiction or nonfiction, I’ll sink into it over many months. I’ll change my routine. That’s the variable that really matters.

But at the same time, when you’re in the weeds, it’s a very different quality of weeds, and for me, fiction is really where my heart is. I do love being in my imagination and not worrying all the time if altering one word altered the meaning in a way that deviates from the facts. In nonfiction, your imagination is a little bit tempered. But in fiction you have to be careful not to stumble onto non-truth.

DS: I agree. Fiction is complete freedom, but you don’t know where to build the structure, and in nonfiction, everything already exists. All Else Failed required years of research, mostly in terms of interviewing refugees and volunteers (and refugee volunteers), but every single interview complicated and expanded my understanding of displacement and how we address it. I loved the challenge of integrating that research in a way that was interesting and compelling. How was it for you? In Who Gets Believed?, a lot of your research is legal and medical and it’s really tricky.

DN: This is what I was saying about not being able to fully turn on your imagination. In one of the stories in Who Gets Believed?, the story about the autistic man who gets interrogated by the police, he falsely confesses, and he has been in jail for 23 years. He recently had his case refused by the Supreme Court of Virginia. I had that excerpt adapted for Time magazine and the legal read was so very different [than the legal read for the book]. There were lawyers arguing over words. Because my voice has been stripped out, so it wasn’t as obvious [that] these are all my opinions. We argued for ages over whether or not we can say “the police report was then altered,” or “then amended,” or “then updated.” I was working with the Innocence Project and the man’s lawyers and we argued that it was a lie to say it was “updated.” The legal team called it an accusation to use “altered,” and I had to, as a writer, come in and say “altered” and “amended” are synonyms. There was no room for saying I don’t like “amended” for aesthetic reasons. That just loses.

In fiction, I look for the best word for the story, for the aesthetics. It feeds and nourishes a different part of you. This is the reason why I need fiction.

DS: There are certain parts of the book where you use your imagination. You talk about a caseworker. You don’t know her background, but you say, I imagine that she grew up in this kind of situation. So, you’re allowing us to see her as an individual even though you didn’t know these things yourself. That’s empathetic. You might be wrong, but you’re trying to talk about a specific person as well as a generalized one.

DN: Exactly. This is one of the things about creative nonfiction that has blossomed in the last twenty, thirty years. When I teach my students, I talk a lot about “perhaps-ing.” What if this person thought this? It’s a different service to the truth than what journalists do.

DS: But it’s also completely honest. There has been criticism of creative nonfiction that it doesn’t allow the reader to understand that it’s speculative. That’s problematic. With perhaps-ing, you’re asking the reader to come with you on a journey, wondering about something in an honest, truthful way. It’s also interesting literarily. Nonfiction can be very heavy. When you try “perhaps-ing,” it allows the prose to take flight in a transparent way.

DN: I like the idea of it taking flight. You have to have something that allows you to fill the cracks in the walls.

DS: Exactly! It makes reading more enjoyable, too.

DN: The storytelling aspect is what draws people in. We can’t continue to preach to people about important world issues through just rhetoric. Storytelling has the necessary elements.

DS: I agree. The storytelling helps the reader understand more than the abstract theory. Empathy comes from feeling that someone is like you and that is from the storytelling.

DN: The storyteller has no agenda.

DS: I have a question about memoir. My first book was a memoir about my experience living in Vietnam, so it’s personal and very intimate. In it, I described my relationship with my Vietnamese boyfriend and the challenges of that. After I wrote the book, readers would say to me, “How is he doing? What is going on with him?” They are complete strangers to me, but they knew me through my writing. Do you have this experience with memoir where the intimacy becomes uncomfortable for you later?

DN: Absolutely. It’s necessary to write for your ideal imagined reader, not for this vast audience. Your book becomes worse if you start to imagine the scrutiny. In fact, everything I regret in my memoirs are things I toned back or changed because I was anticipating a reaction. Every place where I sank into the honesty, at the end of the day, from the aesthetic and literary point of view, I don’t regret it. But it is uncomfortable after you emerge, and people suddenly have access and make comments. I’ve learned to separate myself. You learn that there’s nothing about you that’s so new. Who hasn’t done all this before? Is this really as embarrassing as I think it is?

DS: The thing that makes a memoir different from just a person telling their life story is the writer’s ability to universalize it and grapple with the complexity in a way that’s meaningful to the reader. In your book, you write about how your partner’s brother, Josh, died by suicide. Your relationship with him was very complicated, and throughout the book you allowed for that complexity, even after he died. That’s not a question of simply describing some sad story. You showed the real challenges you faced emotionally. I admire that. I’m wondering how it was for you to write that.

DN: The purpose was to have an impact. I suddenly realized that I was writing a book about believing vulnerable people, and I had not believed this vulnerable person. How can I possibly write this book without owning up to that? [I wanted to] have the gut punch of how wrong you can be even when you believe yourself to be the expert. That’s an important lesson. For others it could be [about] refugees or any group of people you tend to disbelieve. [My partner] Sam said, “If you write this, you shouldn’t let yourself off the hook about the things you didn’t believe.” Now, the book is done, and I feel like at some point, I would like to be let off the hook. I am human.

DS: A book is finished, but it can have continuing resonance.

DN: You’re capturing a moment. Your first memoir was well before mine, how long ago?

DS: Oh gosh, it came out in 2000.

DN: So now that twenty years have passed, I wonder is there any aspect of it that you regret? Have you re-read it?

DS: I haven’t. I’m sure I would write a different book now.

DN: I’m finally reaching that point where you look at your first book and you’re like, I hate this so much. But you would at some point accept that you will feel about every book this way forever.

DS: Your books are like your children, and you have different reactions to them as time goes on.

DN: So, what is your favorite?

DS: I don’t have a favorite. Do you?

DN: Let’s not count the fact that your favorite is really always the next one. Putting those aside, my favorite is The Ungrateful Refugee. What are you writing now?

DS: A novel about a family and music. When I started writing, I wanted to learn about classical music so I made my characters musicians. I did this whole deep dive into classical music. Novels allow you to do that if you like to research.

DN: It is fun. One of the most fun and daunting parts is the understanding that when you’re first learning about something, the way you speak about it is not the way the practitioners speak. They don’t use big terminology, and they have a hundred words that they replace other words with. So, you have to go and listen to those people and that’s really fun.

DS: You get to dip in and out in the way you want. As writers, we don’t have to become experts on every subject.

DN: That’s why I stick close to my experience. I have written about a musician before. I felt like I had to give it to five musicians and ask them to look at the dialogue.

DS: As a writer, you can use a couple of sentences and look like you know a lot more than you do. It stands in for the career knowledge of being a life-long concert pianist.

DN: I think we have ways of gesturing toward something that is just enough.

Dina Nayeri is the author of two novels and two books of creative nonfiction, most recently Who Gets Believed?. A 2019-2020 Fellow at the Columbia Institute for Ideas and Imagination in Paris, and winner of the UNESCO City of Literature Paul Engle Prize, Dina has won a National Endowment for the Arts literature grant, the O. Henry Prize, and was selected for The Best American Short Stories, among other accolades. Her work has been published in more than twenty countries and in the New York Times, the Guardian, the New Yorker, Granta, and many other publications. Dina has degrees from Princeton, Harvard and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. She was born in Iran and currently lives in Scotland, where she teaches at the University of St Andrews.

Dana Sachs is a journalist, novelist, and cofounder of the nonprofit Humanity Now: Direct Refugee Relief, which supports grassroots teams providing aid to displaced people. A former Fulbright Scholar, she is the author of three works of nonfiction, The House on Dream Street: Memoir of an American Woman in Vietnam; The Life We Were Given: Operation Babylift, International Adoption, and the Children of War in Vietnam; and All Else Failed: The Unlikely Volunteers at the Heart of the Migrant Aid Crisis, as well as the novels If You Lived Here and The Secret of the Nightingale Palace. Her writing has appeared in numerous publications, including the Wall Street Journal, National Geographic, and Mother Jones. Sachs lives in Wilmington, North Carolina.