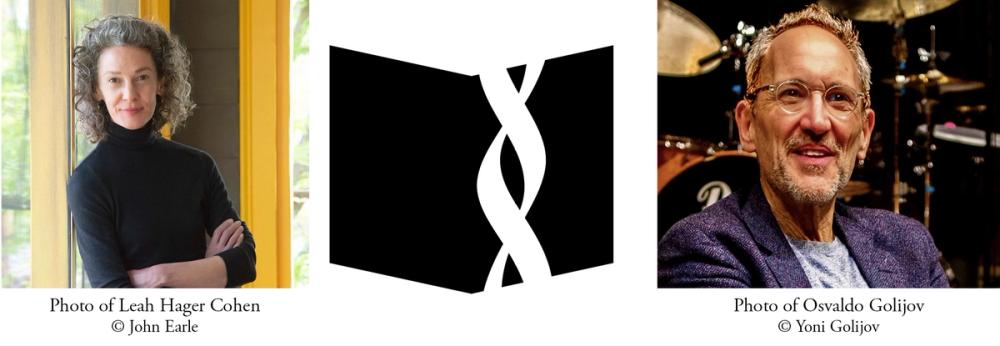

BLP Conversations: Leah Hager Cohen and Osvaldo Golijov

In this conversation Leah Hager Cohen, author of To & Fro, and Osvaldo Golijov, composer of LAIꓘA, discuss cosmonauts, unresolved questions, and how art helps us envision what we can become. Their conversation is part of the BLP Conversations series from Bellevue Literary Press, featuring dialogues that explore the creative territory at the intersection of the arts and sciences.

On April 7, 2024, at Carnegie Hall’s Weill Recital Hall, countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo and The Met Orchestra Chamber Ensemble presented the world premiere of Osvaldo Golijov’s LAIꓘA, written for Costanzo and the Ensemble, with lyrics by Leah Hager Cohen.

Laika, a Soviet space dog, was the first animal to be sent into orbit around the earth, in 1957. Taken from the streets of Moscow as a stray, she would go on to be memorialized in storybooks, statuary, stamps and other branded merchandise. Later it was learned she had died just hours into the flight.

LAIꓘA

by Leah Hager Cohen

A slice of winter sun

Bright gold – eyes closed – all nose

Sifting scents from the cold

The moon, the rain – so strange

to think a street dog could ever miss

the rain

Heaven for a dog

Is this world only

Sausages

Black bread

Chicken dumplings

Chicken grease

The salty skin of the scientist

Who offered his palm for me to lick

And snapped a chain around my neck

Even that was good

Not so this orbiting womb

No brothers no sisters

No mother’s coursing blood

The only heartbeat here is mine

It is speeding speeding

Speeding.

Matchboxes

Chocolates

Razor blades

Watches

Postcards

Cigarettes

Statues

Stamps

You stole me from the street

To cast me in history

What use is history to a dog?

Life for a dog

Is this moment only

Did you really imagine me

As I burn in my orbiting coffin

pondering the wish

of Adyla Kotovskaya who

the night before my flight

wept

kissed my nose

begged forgiveness?

Leah Hager Cohen: I’d never heard of Laika until you taught me about her. How did it begin for you, this desire to write a piece about her and the Soviet space dog program?

Osvaldo Golijov: When I was a child I was fascinated with astronauts, I guess nothing unusual for a boy growing up in the sixties. So I would absorb anything that had to do with them, and I discovered that the Soviets actually called their spacemen (they were all men then) “cosmonauts,” which I thought sounded better.

And then! I discovered that before the Soviets felt secure enough (but still wanting to beat the Americans to it) to send into space their first cosmonaut, Yuri Gagarin, they had experimented with dogs, and that the first dog they sent to space was Laika, a street dog from Moscow. The Soviet Space Dogs were all stray street dogs from Moscow. Small in size to fit the capsule, their teeth pulled out so they wouldn’t bite their tongues in space, their food chewed up and mouth fed by the scientists who experimented on them. One day they were roaming the streets of the city for food, the next day they were in the lab, flying in artificially created zero gravity, and the next day out there in the universe, and Laika (her name is derived from “bark” in Russian), I think, was the first ever earthling in space. She died in space, “for our sake” (“our” being the human capacity to go into space, or Soviet glory, or both).

At the time the Soviets told everyone that she died peacefully after five to seven days in space, euthanized as her oxygen supply would dwindle. A great contemporary myth was born. I think only in 2002, 45 years after her death, one of the scientists in the program revealed that she had burned to death only about five to seven hours after the launch. The scientists apparently needed about an extra month to develop a method of peaceful death for Laika, but Nikita Kruschev (the Soviet leader at the time) was adamant that the launch had to happen on October 17, 1957, on the 40th anniversary of the revolution. Other dogs went to space after Laika and came back alive. Among them were Belka and Strelka (Squirrel and Little Arrow), who became celebrities and would give interviews on Radio Moscow after their return. Strelka had several puppies after the flight; one of them was called Pushinka and was given as a present by Kruschev to President Kennedy in 1961. So if nuclear war had happened because of the Cuban Missile crisis in 1962, Pushinka would have probably died then, far from home. As it happens, nuclear war didn’t happen, and Pushinka mated with Charlie, one of Kennedy’s dogs, and they had four puppies whom Kennedy called pupniks and apparently lived happily ever after. Two of them, Butterfly and Striker, were given to children in the Midwest and kept multiplying, with proven descendants until at least 2015.

The Soviet Space Dogs were big heroes in Argentina, where I grew up, and in many other places in the world. All kinds of memorabilia sprung up, as you noted in some of my favorite lines of your Laika poem: “matchboxes, chocolates, razor blades, watches, postcards, cigarettes, statues, stamps…” If you were a stamp collector in Argentina, as I was when I was a boy, and had a Laika stamp in your collection… Well, I would venture that it was worth much more than what a Pikachu card is worth today. So yes, to give you an idea of how impactful the Soviet Space Dogs were in the imagination of a child far away from Moscow, just think of Yuri Gagarin, the first cosmonaut mentioned above. He said, “I don’t know if I am the first man or the last dog in space.” That line alone is worth an opera.

You know, I think one thing that links LAIKA and To & Fro is that the three stories are journeys (maybe you think of To & Fro as only one story with two faces? I’d love to know how you think of it). So I have two questions (three if you count the one I just asked): can you tell us about the journey in To and the journey in Fro? And how and why is it that there are no bad guys in your stories? I think especially in To… I feared so much for the dangers that Ani might encounter in her journey and even if she met many savory characters, with poignant humor and tender roughness, it’s all good people!

LHC: When you asked me to write a poem about Laika for this project, although I had heard you talk about her before, that was the first time I did any research on my own. And one thing I found was the teeth thing—apparently the dogs didn’t have their teeth pulled before going to space. It was after returning, for those who made it back alive, that the teeth fell out due to calcium depletion from the ordeal of being in space. Or at least one dog, Veterok, lost his, and the scientists would pre-chew sausage for him as he lived out the rest of his days on earth. I mention this because of what you say about “a great contemporary myth” being born. This fascinates me, the human tendency to mythologize, the way we take actual events and—often quite unintentionally—make stories of them. The changes that take place during this move from event to story can tell us so much about ourselves.

Of course, artists are in the business of doing this intentionally. Distilling something to its essence (or one version of its essence) and then presenting it back to us in a different form, strange and fresh. You’ve done this with Jesus, Lorca, bereavement, the cosmos… and now Laika. You dip your cupped hand into the swirly waters of life, lift something up, and translate it into music. You create something new without ever depleting the source. It’s like having one’s cake and eating it, too.

As for journeys and To & Fro, I like what you say about one story with two faces. In fact, one idea in the novel is that “it’s all one story.” You dip your hand in the swirly water, and I dip my hand in the same swirly water, and it’s the same swirly water for everyone! Nina Simone and Chekhov and Beethoven and Olga Tokarczuk and Mahmoud Darwish and Matisse and Basquiat and Eavan Boland and everybody, from little kids drawing with chalk on the sidewalk to those you like to call the Great Motherfuckers. That makes me so happy. We’re all working with the same undepletable source material, which is the experience of being a human in the universe, and we make this infinite variety of different things with it. And that’s the journey. And everyone can do it.

Sorry, what was the question? Oh yeah: why no bad guys.

That’s an important question, because the harm we do one another in this world is real and must be grappled with, and I would hate to think I’ve avoided something in my work from a lack of courage. On the other hand, an awful lot of representational art—especially that which is commercially successful—centers violence. If art helps us envision what we might become, then I think there’s a place for works that imagine alternative visions, too. I didn’t set out to write a book in which the two protagonists are young girls who never encounter the threat of harm, but in retrospect, I think the politics of that are strong. By politics, I mean simply that every act of self-expression is colored by the context in which it takes place, and contributes in some way to the community in which we live. What are the politics of LAIKA for you—not the dog but your composition? Do you hate this question, do you reject the premise? Even so, will you say something about what it brings up for you?

OG: I like it when you say, “if art helps us envision what we might become.” It reminds me of something Wayne Shorter said, I think, to Danilo Perez: “Write the music for a world in which you’ll want to live.” Sometimes I forget it, so thank you for reminding me.

What are the politics of LAIKA for me? It’s not that I hate the question, but I know that I will not be able to articulate in words all the themes in the constellation of themes that LAI ꓘA represents for me. Mainly I’d say that Laika the dog didn’t want to be a hero. I think she liked her street dog fate. I can’t say for sure, since I don’t know the street dogs in Moscow, but the ones in La Plata, the city where I grew up, seemed pretty happy to me in their street wanderings. That’s why I love the first refrain in your poem: “sausages / black bread / chicken dumplings / chicken grease”! You mentioned Lorca. He didn’t want to be a hero either. His entire reason to write his play Mariana Pineda (a woman who was executed a century before Lorca himself was executed, part of the plot of Ainadamar) was to bring Mariana back to life, take her out from the statue that people who need heroes built for her (“she was not gray, not cold, not even pure,” as David Hwang’s libretto puts it). I think most people would prefer love to heroics (but of course many heroic acts are acts of love, so it is complex). Dogs for sure, they are love. In any case, I don’t know if what I just said relates to the politics of LAIꓘA. I can only tell you the unresolved questions that LAIꓘA brings out in me: the nature of love, the nature of power, the paradox of loving dearly a child or a dog and sending them to die in a war or in a space capsule, the need for heroes we spoke about, and other things. But mainly, I wrote it because I wished to collaborate with you on this long song and had (and have) a great curiosity to see what Anthony Roth Costanzo does when singing as Laika.

But I am even more curious about To & Fro than I am about LAIꓘA. Do you know why Ani steals a kitten? How did it ever occur to you to write an entire novel out of a short parable by Kafka? Do you remember? You know I love the Ferryman so much, and I don’t want to introduce spoilers here, but how did you come up with him and his sense of humor? Yes, that’s another reason I love To & Fro: there’s so much banter going on.

LHC: I love your move from politics to unresolved questions. Politics, as I was using it, invites thinking about the relationship between artwork and society—the society in which the art is created, and the society into which it will venture forth. “Unresolved,” as I hear it, suggests something at once far more intimate and limitlessly large: the relationship between soul and wonder. And there is room here for everything, isn’t there? Love and paradox, children and dogs, war and space and heroes and myths and duets and sausages.

I hear that in your music. Intimacy and infinity. When I am writing I am in a state of not-knowing; this makes me very bad at responding to questions about what I have done and why.

I did not realize Ani was going to steal a kitten until it happened, as it were, in the writing. As if I myself were the girl in the story, I had the experience, while writing, of “looking down” and seeing the kitten there on “my” palm.

And it never occurred to me to spin an entire novel out of a parable by Kafka. If the prospect had presented itself like that, I probably would have fled in terror. What happened was that I simply found myself—almost idly, almost without noticing what I was doing—sketching out a kind of scene in which I picked up where his parable leaves off.

The ferryman, too. I don’t feel I “made” him. It was as if he already existed, and I had only to feel my way toward where he entered, and to listen really, really well to how he sounded, what he looked like, how he walked and smoked his pipe and harrumphed and was gruff and, underneath the gruffness, was a big gentle softie.

And thank you! Because your question has surfaced something very central to the book, which is the idea of the artist “making” something versus midwifing something into being. The latter contains the sense of that something being already alive, having a life of its own, and being imbued with a mystery the artist neither designed nor can ever fully resolve. (Speaking of unresolved questions.)

This is a key part of Annamae’s story. With a kind of spiritual stubbornness she is unable to explain, she refuses to complete her English teacher’s creative writing assignment, which she sees as forcing her to make something inert and false, akin to engaging in idolatry. I love Annamae’s stubbornness. The irony isn’t lost on me that she, a fictional character of my own “making,” rails against the notion of creating fictional characters, who by definition lack free will.

Not even God, she says, would do such a thing.

What gives me solace is the possibility that she’s neither inert nor entirely of my making. Because she continues to puzzle and beguile me, and I can continue to learn from her…

OG: And thank you!

Osvaldo Golijov’s works include the St Mark Passion; the opera Ainadamar; Azul, a cello concerto; The Dreams and Prayers of Isaac the Blind, for clarinet and string quarter; the song cycles Ayre and Falling Out of Time; and the soundtracks for Francis Ford Coppola’s Tetro, Youth Without Youth, and the upcoming Megalopolis. His most recent works include LAIꓘA, written for Anthony Roth Costanzo and the Met Orchestra Chamber Ensemble, and The Given Note, a work for violinist Johnny Gandelsman and The Knights. He is currently working on Megalopolis Suite for Riccardo Muti and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. He was born in La Plata, Argentina, in 1960, and lived in Jerusalem before immigrating to the United States in 1986. He is the Composer-in-Residence at The College of the Holy Cross.

Leah Hager Cohen is the author of seven novels, including To & Fro, and five works of nonfiction, including Train Go Sorry. Among other honors, her books have been longlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction, named a finalist for the Dayton Literary Peace Prize, and selected as best books of the year by the New York Times, Washington Post, San Francisco Chronicle, Globe and Mail, Christian Science Monitor, and Kirkus Reviews. Cohen is the Barrett Professor of Creative Writing at the College of the Holy Cross. She lives in Belmont, Massachusetts.