[Dr. Reicher] lived through the Second World War in Poland, dodging bullets, uprisings and deportations—not to mention betrayal, starvation and airless hideouts—in a manner more reminiscent of a talented outlaw than a mild-mannered dermatologist . . . It is the impressive simplicity of the good doctor’s writing that makes [t]his book resemble [Victor] Klemperer’s, and the detailed observations of its report that makes it emotionally memorable. . . . William Carlos Williams once said that people who prize information are perishing daily for want of the information that can be found only in poetry. By the same token, there will never be a time when we will not need the information that an important, evocative book like Country of Ash provides.

Country of Ash

A Jewish Doctor in Poland, 1939-1945

Country of Ash is the gripping chronicle of a Jewish doctor who miraculously survived near-certain death, first inside the Lodz and Warsaw ghettoes, where he was forced to treat the Gestapo, then on the Aryan side of Warsaw, where he hid under numerous disguises. He clandestinely recorded the terrible events he witnessed, but his manuscript disappeared during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. After the war, reunited with his wife and young daughter, he rewrote his story.

Peopled with historical figures from the controversial Chaim Rumkowski, who fancied himself a king of the Jews, to infamous Nazi commanders, to dozens of Jews and non-Jews who played cat and mouse with death throughout the war, Reicher’s memoir is about a community faced with extinction and the chance decisions and strokes of luck that kept a few stunned souls alive.

Ebook

- ISBN

- 9781934137598

Paperback

- ISBN

- 9781934137451

In the Passover edition of The Forward, Austin Ratner writes about the legacy of the Warsaw Ghetto, the psychology of bigotry, and the parable he found within Edward Reicher’s memoir, A Country of Ash, musing “that there would perhaps be fewer great sins in the world if people were not so frantic to purify themselves of small ones.”

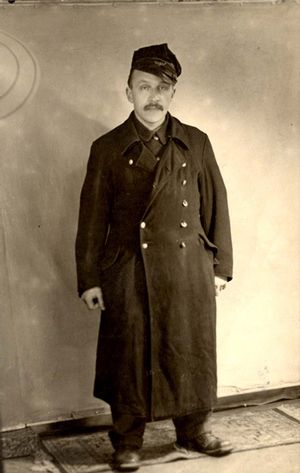

Edward Reicher (1900–1975) was born in Łódź, Poland. He graduated with a degree in medicine from the University of Warsaw, later studied dermatology in Paris and Vienna, and practiced in Łódź as a dermatologist and venereal disease specialist both before and after World War II. A Jewish survivor of Nazi-occupied Poland, Reicher appeared at a tribunal in Salzburg to identify Hermann Höfle and give an eyewitness account of Höfle’s role in Operation Reinhard, which sent hundreds of thousands to their deaths in the Nazi concentration camps of Poland.

His memoir, Country of Ash, was first published posthumously in France thanks to the efforts of his daughter Elisabeth Bizouard-Reicher.

Translator Magda Bogin is acclaimed for her “suave” (Publishers Weekly) and “strikingly true” (School Library Journal) translation of Cervantes’ Don Quixote, Isabel Allende’s international bestseller The House of Spirits, and letters by children deported to Auschwitz, which appear in the landmark publication French Children of the Holocaust. Bogin’s own novel, Natalya, God’s Messenger, received the Harold U. Ribalow Prize. She lives in New York.

Praise for Country of Ash

It’s the rough texture of Reicher’s tale—like grainy celluloid from a bygone era—that gives such a powerful, deeply disturbing immediacy to the ghetto inhabitants he remembers. Reicher tells us they’re no more, but he is wrong. Their ghosts still walk in books like this one—haunting the reader, forever.

Edward Reicher recorded his Holocaust nightmares from the ghettos of Lodz and Warsaw to the chilling attempts for his family to live as Aryans in a world of blackmail, informants and circumcision checks. . . . ‘This book has no literary pretensions,’ he writes. ‘It is the description of the life of a Jewish doctor who survived the worst years.’ Yet it’s far more than that . . . Country of Ash is worth reading because the riveting survival drama is framed by larger questions.

What makes this diary so powerful is that Reicher dwells on very little—for it is all so crazy—and tells the facts and his story with dispatch, so that we are so caught up in events that we begin to feel as if we are living them with him, that we have somehow been dropped into a Beckett or Ionesco play where absurdity at its most extreme is reality. . . . We can give thanks to all who worked to bring Country of Ash into our lives, then read it with care, and heed its warnings.

Country of Ash is not only a tribute to strength, determination, and fortitude, but a tribute to all of the Jewish victims of the Holocaust. It is a tribute to those who were not Jewish, yet did strive to offer a place to hide and offer food to Reicher and/or his family. It is a memoir that honors Reicher’s daughter, Elisabeth Bizouard-Reicher’s determination to see her father’s memoir in print for all the world to read . . . [It is] a brilliantly written account.

Recounts the story of how Edward Reicher, a distinguished prewar dermatologist and venereal disease specialist escaped the Lodz and Warsaw Ghettos with his wife and young daughter. While on the surface Reicher’s memoirs describe the many disguises and hiding places he and his family used in order to avoid the Gestapo and Polish Blue Police, the deeper message of this work concerns the almost universal ‘moral failure’ that permeated the non-Jewish Polish population.

A riveting first-hand account of the destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto. Edward Reicher presents events from the perspective of a Jew, a physician, a survivor, a chronicler, a husband but mainly a humanitarian caught in the flux of horrific events that, but for memoirs such as this, would fade with the absolution of time. Reicher’s astonishing book insures that will not happen.

— Arthur L. Caplan, Ph.D., Drs. William F. and Virginia Connolly Mitty Chair Director, Division of Medical Ethics, NYU Langone Medical Center and author of When Medicine Went Mad: Bioethics and the Holocaust

Dr. Reicher’s memoir tells a gripping, tragic, unforgettable tale that, like Wladyslaw Szpilman’s The Pianist, recounts the horrors of being a Jew in Poland during World War II. This important historical document distinguishes itself from other Holocaust narratives in many ways, but perhaps in none more so than this: its perseverant hero not only saved his wife and daughter but helped bring one of the most notorious Nazis of all to justice.

— Austin Ratner, Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature-winning author of The Jump Artist and In the Land of the Living