The Cage is a tightly written and clear-eyed narrative about one of the most disturbing human dramas of recent years. . . . A riveting, cautionary tale about the consequences of unchecked political power in a country at war. A must-read.

— Jon Lee Anderson, New Yorker staff writer and author of The Fall of Baghdad

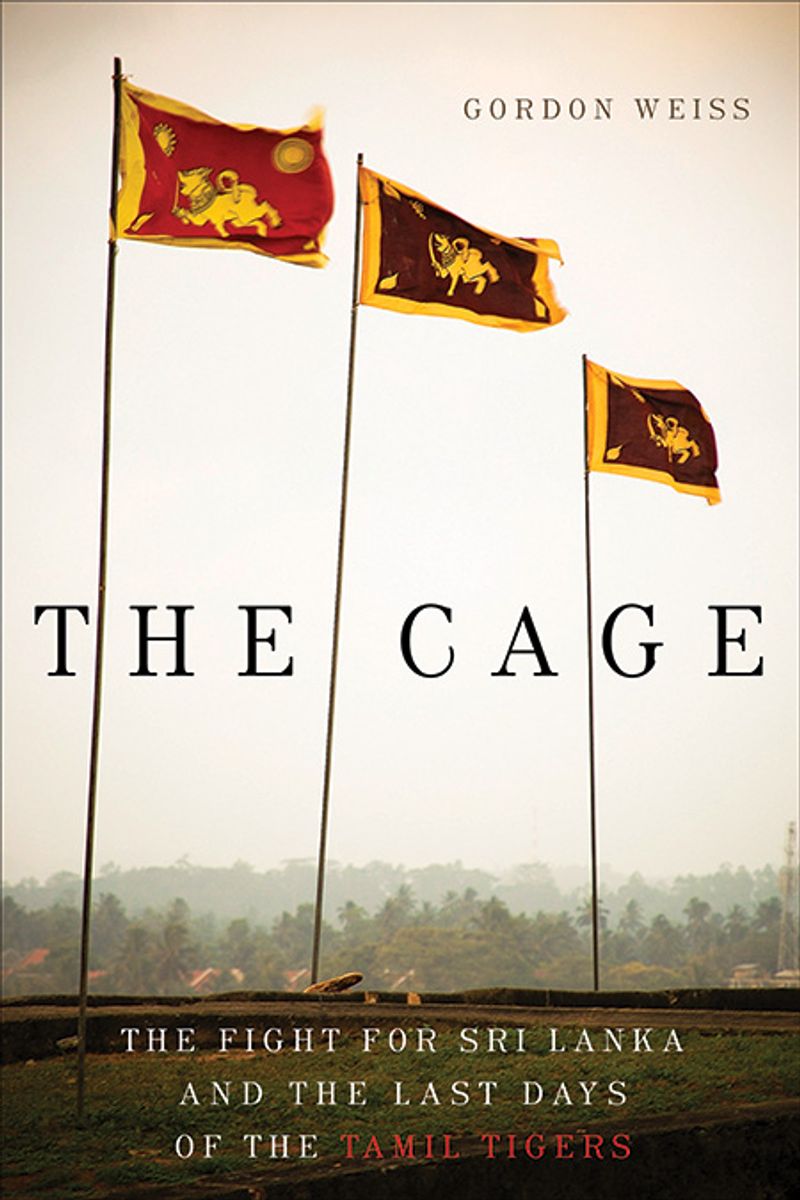

The Cage

The Fight for Sri Lanka and the Last Days of the Tamil Tigers

In the closing days of the thirty-year Sri Lankan civil war, tens of thousands of civilians were killed, according to UN estimates, as government forces hemmed in the last remaining Tamil Tiger rebels on a tiny sand spit, dubbed “The Cage.” Gordon Weiss, a journalist and UN spokesperson in Sri Lanka during the final years of the war, pulls back the curtain of government misinformation to tell the full story for the first time. Tracing the role of foreign influence as it converged with a history of radical Buddhism and ethnic conflict, The Cage is a harrowing portrait of an island paradise torn apart by war and the root causes and catastrophic consequences of a revolutionary uprising caught in the crossfire of international power jockeying.

Foreign Affairs Book of the Day

Spectator & Intercept Summer Reading List selection

Paperback

- ISBN

- 9781934137543

Ebook

- ISBN

- 9781934137574

Gordon Weiss provides perspective about human rights abuses and the ongoing war crimes investigation in Sri Lanka with Radio New Zealand and on a harrowing ABC broadcast detailing new allegations of torture.

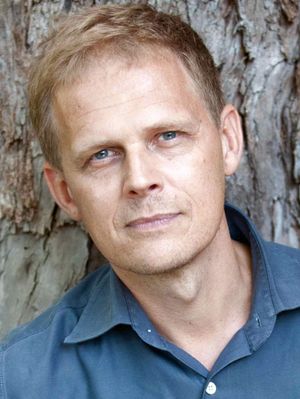

Gordon Weiss has lived in New York and worked in numerous conflict and natural disaster zones including the Congo, Uganda, Darfur, Bosnia, Afghanistan, Syria, and Haiti. Employed by the United Nations for over two decades, he continues to consult on war, extremism, peace building, and human rights. The Cage: The Fight for Sri Lanka and the Last Days of the Tamil Tigers is his first book.

Praise for The Cage

Mr. Weiss accurately lays out the central challenges that regional actors, nongovernmental organizations and the international community face in Sri Lanka: ensuring accountability for possible war crimes, and a life of dignity and equality for all Sri Lankan citizens. . . . This powerful book is a haunting reminder of the price countries in the developing world pay for the flawed choices of their founders.

Weiss excels at chronicling the changes in attitude of the post-9/11 world and the changing geopolitical landscape. . . . For those interested in this modern human rights tragedy and how basic political rights get shredded by both the government and the freedom fighters, then The Cage is a must read.

A striking account of the ruthless terror wreaked by both sides on the innocent civilians.

— Sunday Times

An accessible and compelling narrative of Sri Lanka’s often violent and tortured history. . . . Weiss pulls no punches in tackling the atrocities committed by the Tigers. But he is equally scathing about the failure of the successive Sri Lankan administrations to deal with the aspirations of the Tamil minority and brutal tactics employed by the Sri Lankan Army to quash the rebellion.

[The Cage] raises . . . the question of how witnesses should respond to alleged war crimes, human rights violations, and the breakdown of the rule of law. A sweeping discussion. . . . Weiss deftly sketches the main issues for a general audience while also providing a solid bibliography and detailed endnotes. The book will appeal to readers interested in Sri Lanka, South Asia, political science, military history, and international relations.

— Asian Ethnology

Some of the best coverage of Sri Lanka right now is coming from Gordon Weiss.

— Nick Bryant, BBC News correspondent

This shattering, heartbreaking tale of savagery and suffering not only lifts the veil that conceals one of the most awful tragedies of the current era, but also helps us understand what should be done, not just in this sad and beautiful land, but long before other such horrors spiral out of control.

— Noam Chomsky, Institute Professor & Professor of Linguistics, MIT, and author of Hopes and Prospects

The Cage is a comprehensive and compellingly readable account of one of the very worst atrocity stories this century. Gordon Weiss is scrupulously evenhanded in describing the terrible excesses of the Tamil Tigers as well as the Sri Lankan authorities. His book is a timely prod to the world’s collective conscience.

— Gareth Evans, former Foreign Minister of Australia, Co-Chair of the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty, and author of The Responsibility to Protect: Ending Mass Atrocity Crimes Once and For All

When I was commissioned to do this report, the first thing I was handed was a copy of The Cage. Weiss’s scrupulously balanced account should serve as a guidepost for decision-makers and scholars of international affairs. A book can change the world.

— Charles Petrie, diplomat and author of the United Nations “Petrie Report” into the UN’s role and responsibilities during the Sri Lankan conflict

A fair and brilliantly written tour de force of this long forgotten war. A book that is long overdue.

— Roma Tearne, author of The Mosquito