An excellent piece of science writing. . . . Cassidy does not so much exculpate Heisenberg as explain him, with a transparency that makes this biography a pleasure to read.

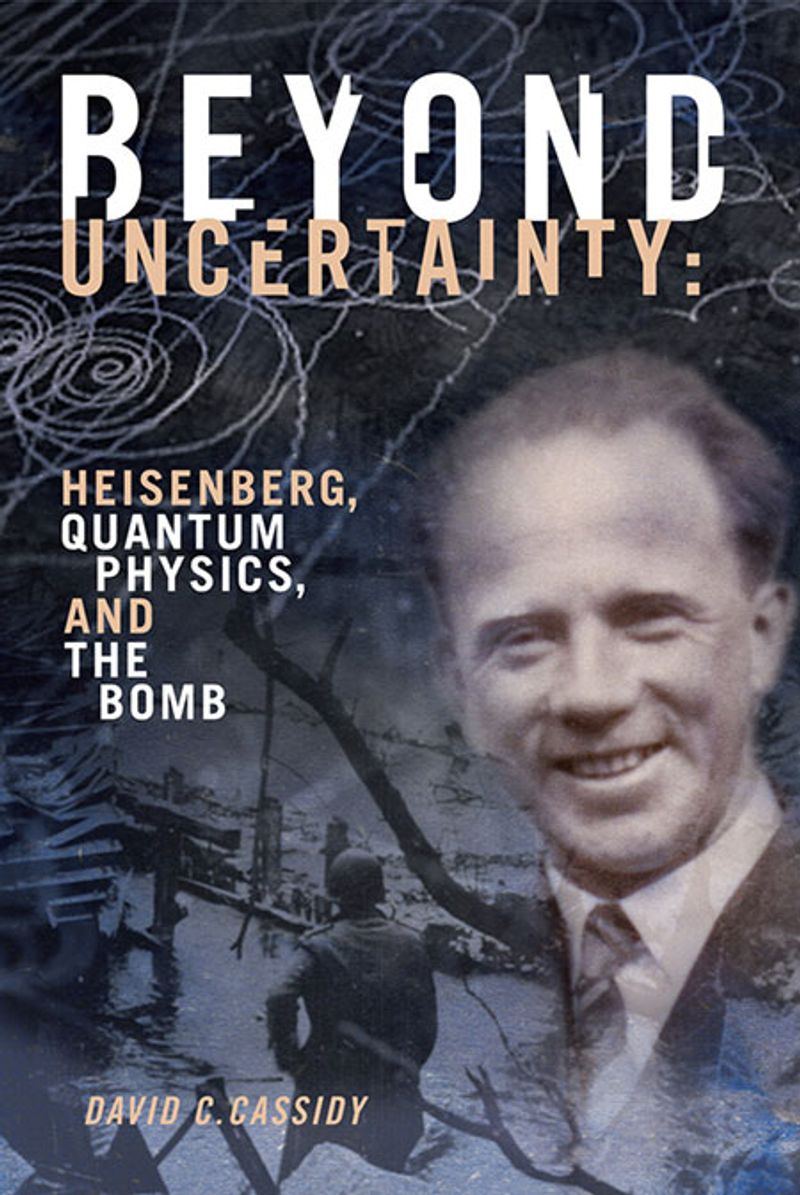

Beyond Uncertainty

Heisenberg, Quantum Physics, and The Bomb

In 1992, David C. Cassidy’s groundbreaking biography of Werner Heisenberg, Uncertainty, was published to resounding acclaim from scholars and critics. Michael Frayn, in the Playbill of the Broadway production of Copenhagen, referred to it as one of his main sources and “the standard work in English.” Richard Rhodes (The Making of the Atom Bomb) called it “the definitive biography of a great and tragic physicist,” and the Los Angeles Times praised it as “an important book. Cassidy has sifted the record and brilliantly detailed Heisenberg’s actions.” No book that has appeared since has rivaled Uncertainty, now out of print, for its depth and rich detail of the life, times, and science of this brilliant and controversial figure of twentieth-century physics.

Since the fall of the Soviet Union, long-suppressed information has emerged on Heisenberg’s role in the Nazi atomic bomb project. In Beyond Uncertainty, Cassidy interprets this and other previously unknown material within the context of his vast research and tackles the vexing questions of a scientist’s personal responsibility and guilt when serving an abhorrent military regime.

Ebook

- ISBN

- 9781934137321

Paperback

- ISBN

- 9781934137284

David C. Cassidy is the author of Beyond Uncertainty: Heisenberg, Quantum Physics, and the Bomb; A Short History of Physics in the American Century; J. Robert Oppenheimer and the American Century; and Einstein and Our World. He is the recipient of the Abraham Pais Prize for History of Physics from the American Physical Society, the Science Writing Award from the American Institute of Physics, the Pfizer Award from the History of Science Society, and an honorary doctorate from Purdue University. Dr. Cassidy is professor emeritus of natural sciences at Hofstra University and resides in Bay Shore, New York.

visit author page »Praise for Beyond Uncertainty

An excellent work in its comprehensiveness and accuracy, and in its success in recreating the personal drama of one of the greatest and most influential scientists of this century.

— Times Higher Education

An excellent follow up on Cassidy’s earlier masterwork Uncertainty. Cassidy offers deep insight into Heisenberg’s role as a principle founder of quantum mechanics and as the leading German physicist during the WWII years in the quest for atomic energy and weapons.

— Benjamin Bederson, physics professor emeritus, New York University, editor-in-chief emeritus of the American Physical Society, and Manhattan Project member

A must read book about key players in science and world history.

— Gerald Holton, research professor of physics and history of science, emeritus, Harvard University, and author of Einstein, History, and Other Passions and coeditor of Einstein for the 21st Century

Cassidy has written the definitive biography of a great and tragic physicist.

— Richard Rhodes, author of the Pulitzer Prize–winning The Making of the Atomic Bomb

An excellent work of scholarship. . . . Cassidy tells this story with nuance and passion.

— Mark Walker, author of German National Socialism and the Quest for Nuclear Power, 1939-49 and Nazi Science