“Some writers are good at drawing a literary curtain over reality, and then there are writers who raise the veil and lead us to see for the first time. Krivak belongs to the latter. The Sojourn, about a war and a family and coming-of-age, does not present a single false moment of sentimental creation. Rather, it looks deeply into its characters’ lives with wisdom and humanity, and, in doing so, helps us experience a distant past that feels as if it could be our own.”

National Book Award judges’ citation

-

on

“A story that celebrates, in its stripped down but resonant fashion, the flow between creation and destruction we all call life.”

Dayton Literary Peace Prize judges’ citation

( link)-

on

“A novel of uncommon lyricism and moral ambiguity that balances the spare with the expansive.”

Chautauqua Prize committee citation

( link)-

on

“The Sojourn is a beautifully told story of a young man’s coming of age in World War I Austria. It is quiet, serene, and filled with humanity, even while recounting scenes of violence and war.”

Miami-Dade Public Library System, Dublin Literary Award Longlist citation

( link)-

on

“[An] exquisite first novel. . . . Full of violence and beauty, Krivak shares a unique story about a boy becoming a man during a tragic period in world history.”

Sherri Gallentine, Vroman’s Bookstore, Indie Next List citation

( link)-

on

“With unforced elegance, this novel renders the journey of a young man who leaves his impoverished shepherd’s life behind for the World War I killing fields of Europe.”

Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers committee citation

-

on

“A gripping and harrowing war story that has the feel of a classic.”

NPR “Year’s Top Book Club Picks” citation

( link)-

on

“Splendid. . . . A novel for anyone who has a sharp eye and ear for life.”

NPR All Things Considered

( link)-

on

“[A] powerful, assured first novel. . . . If the early pages of The Sojourn sometimes recall Cormac McCarthy (especially The Crossing), the heart of the book is a harrowing portrait of men at war, as powerful as Ernst Junger’s classic Storm of Steel and Isaac Babel’s brutally poetic Red Cavalry stories.”

Washington Post

( link)-

on

“A classic of war. . . . Beautifully plotted, as rapt and understated as a hymn.”

Plain Dealer

( link)-

on

“Captivating, thoughtful. . . . A poignant reminder of how humanity was so greatly affected by what was once called the war to end all wars.”

Star Tribune

( link)-

on

“[The Sojourn] deserves to be placed on the same shelf as Remarque, Hemingway and Heller. . . . Krivak has written an anti-war novel with all the heat of a just-fired artillery gun.”

Barnes and Noble Review/Christian Science Monitor

( link)-

on

“A fairly short, brisk story that covers a lot of ground. . . . Beautifully written and uplifting even through all the tragedy.”

Press-Telegram

( link)-

on

“Faith—hope for the future, the conversion of tragedy into meaning—lurks throughout The Sojourn’s lush and lyrical prose.”

Image

-

on

“Unsentimental yet elegant. . . . With ease, [The Sojourn] joins the ranks of other significant works of fiction portraying World War I.”

Library Journal (starred review)

( link)-

on

“Assured, meditative. . . . Krivak has his own voice, given to lyrical observations on the nature of human existence.”

Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

( link)-

on

“Charged with emotion and longing . . . this lean, resonant debut is an undeniably powerful accomplishment.”

Publishers Weekly (starred review)

( link)-

on

“Beautiful. . . . Deftly wrought. . . . Krivak studied all the Great War novels before writing, and the result is a debut novel at home amongst those classics. Highly recommended.”

Historical Novels Review (Editors’ Choice review)

( link)-

on

“The prose echoes Faulkner, and Krivak shows us the little-known Italian front of WWI in fascinating episodes.”

Booklist

( link)-

on

“Rendered in spare, elegant prose, yet rich in authentic detail. . . . [The Sojourn] stands with the most memorable stories about World War I.”

Foreword Reviews

-

on

“The Sojourn is a fiercely wrought novel, populated by characters who lead harsh, even brutal lives, which Krivak renders with impressive restraint, devoid of embellishment or sentimentality. And yet—almost despite such a stoic prose style—his sentences accrue and swell and ultimately break over a reader like water: they are that supple and bracing and shining.”

Leah Hager Cohen, author of The Grief of Others and Strangers and Cousins

-

on

“The Sojourn is a work of uncommon strength by a writer of rare and powerful elegance about a war, now lost to living memory, that echoes in headlines of international strife to this day.”

Mary Doria Russell, author of The Sparrow and The Women of the Copper County

-

on

“Intimate and keenly observed, [The Sojourn] is a war story, love story, and coming of age novel all rolled into one. I thought of Lermontov and Stendhal, Joseph Roth and Cormac McCarthy as I read. But make no mistake. Krivak’s voice and sense of drama are entirely his own.”

Sebastian Smee, Pulitzer Prize–winning art critic

-

on

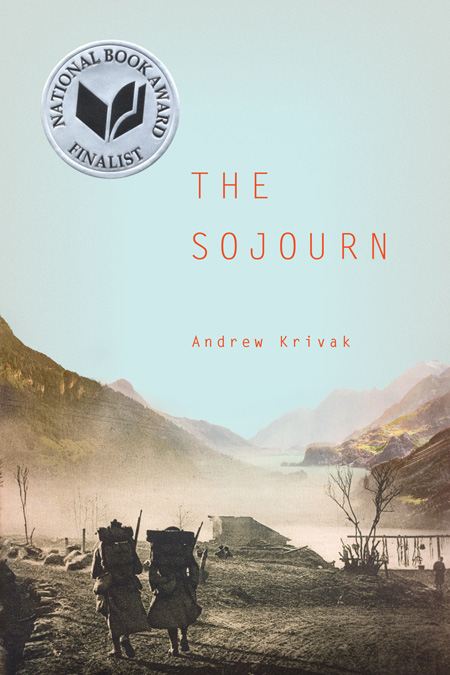

The Sojourn is the story of Jozef Vinich, who was uprooted from a 19th-century mining town in Colorado by a family tragedy and returns with his father to an impoverished shepherd’s life in rural Austria-Hungary. When World War I comes, Jozef joins his adopted brother as a sharpshooter in the Kaiser’s army, surviving a perilous trek across the frozen Italian Alps and capture by a victorious enemy.

A stirring tale of brotherhood, coming of age, and survival, The Sojourn is the freestanding, first novel of Andrew Krivak’s award-winning Dardan Trilogy, which concludes with Like the Appearance of Horses. Inspired by the author’s family history, it is also a poignant tale of fathers and sons, addressing the great immigration to America and the desire to live the American dream amid the unfolding tragedy in Europe.

National Book Award Finalist

Chautauqua Prize Winner

Dayton Literary Peace Prize Winner

Additional Accolades

American Booksellers Association Indie Next List & Indie Next List for Reading Groups * Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers Selection * Dublin Literary Award Longlist * Julia Ward Howe Book Award Finalist * Boston Globe Bestseller

Named One of the Best Books of the Year by

NPR * Washington Post * Plain Dealer * Virginian-Pilot * Barnes & Noble Review

Excerpt from The Sojourn

Three days later we circled back toward divisional headquarters near Görz, and reported in. What we brought the Major (we had to bring him something) was news of recently fortified Italian camps, accompanied by troop movement along the entire western stretch of river, from the Bainsizza plateau down to Görz. Battle was imminent, and the Italians looked determined to make it their last.

It wasn’t their last, though. The Austrians expected a spring offensive, and our scouting confirmed this, but High Command’s best guess was that the Italians would proceed more tactically than they had in the past, using diversionary incursions upstream to draw our divisions holding the three mountains away from higher ground, and then attacking with their seemingly endless supply of troops. But the Italians had learned nothing in two years of fighting, and the Emperor’s generals learned that for all of its ethnic factions, diversities, and desertions, theirs was an army of men who would go to their deaths throwing stones at the Italians rather than give an inch of homeland.

And so it began with little more warning than the suspicious activity Zlee and I and a few spotters reported to our command. At first light

on the twelfth of May, we had just come off a week’s rest and were sitting in a good hide forward of our main trench, from which we had seen an artillery team in range. We wondered why they had exposed themselves so foolishly, but never thought to question our luck. The officer was easy to identify, as his gunners loaded and aimed their cannon. I reckoned him at five hundred and fifty yards, a long shot, but Zlee never second-guessed himself, or me. Windage was light and the morning air dry, and Zlee just brushed the trigger and I watched that man’s head snap back and body crumble as though it had been relieved of its bones.

And hell followed, 3,000 guns – long range, medium, trench mortars, everything – opened fire on us and every other Austrian position from Plava to the Adriatic for two days straight, so that no one or no thing could run, move, or even breathe, a hell in which I prayed to some lost God that I might die so that the banishment toward it would end as quickly as it began.

They say the earth is a soldier’s mother when the shells begin to fall, and she is, at first, your instinct not to run but to dig and hold and hug as much of that earth as you possibly can, down, down, down into the dirt, with your fingertips, hands, arms, chest, thighs and feet, until you are like a child clinging with his entire body to comfort after a nightmare.

But minutes of this, then hours, and days, and you wonder: How many days? Because the earth herself can’t stop shaking and disintegrating as the shrieks and howls rain in like otherworldly miscreations on wing who know – know! – where you are hiding and want not just to kill but to annihilate you, their hissing and infuriate ruts as they approach the last sound you’ll ever hear.

In that initial wave, our forward position saved our lives. Lines flanking us to the right and left took hit after hit and the longer range guns seemed to be inching ahead with each bombardment, stalking our counter-battery fire, command posts, and supply dugouts, so that any response or counter attacks would have to struggle to follow. Yet the Italians seemed interested not in accuracy but fury, and Zlee and I pressed down beneath the cover of canvas we’d used for camouflage and a wall of sandbags we pushed up to take shrapnel for four hours of nonstop shelling, some explosions so close I could feel air being sucked from my lungs.

At what we guessed was late morning there was a lull. We took our chances and threaded through the warren of dugouts, ledges and trenches that made up our forward line, the men still in positions that hadn’t been completely destroyed looking like gray mannequins in a desolate uniform shop, some doe-eyed and terrified, others appearing resigned to their deaths already. The sergeant who had gone out with us to shoot deserters got hauled past on a stretcher by two bearers, his mouth opened in a scream we couldn’t hear (for the bombardment had rendered us deaf) and his chest laid open so clean I could see his heart beating wildly beneath the bones of his rib cage. The captain’s dugout had taken a direct hit. Nothing and no one there by the time we reached it but a horse on its haunches pawing the dirt, and the coppery stink of blood and burnt flesh all around.

By noon the Italians were at full force again, and we had made it to Major Márai’s tent just beyond the reserves. He said he wanted us to stay out of the lines and head back to Mount Santo where they suspected the Italians would attack in strength when the artillery barrage was finished. We were to take any shots we had on high value targets – officers, cannoneers, scouts.

After a day’s hike with a separate regiment, Zlee and I took position on the upper reach of Mount Santo in the ruins of an old monastery’s gate house, long since reduced to rubble by artillery. The night before, we ate field rations of biscuits and hard tack with the same Croats who had fed us when we were ranging from those hills. And at dawn on the fourteenth, the Italians came over the top.

The brigade sent to re-take that mountain knew the mixed terrain on the western slope and had been hiding its regiments among the massive stones and stands of trees under the ongoing cover of artillery fire, so that the soldiers defending the mountain were caught off guard, weakened and shell shocked as they were, as wave after wave of Italian fanti burst from their positions like water from an earthen dam and charged up the steep and bald slopes of those hills, only to be mown down by our Schwarzloses and close range guns. By late morning, men barely seemed to touch the ground as they entered battle and died in one seamless move, so thickly strewn with bodies were those hills. The few that pushed on toward a trench or rock dugout were shot in the face with pistols, gutted with bayonets, or fought hand to hand, bravery and folly indistinguishable on both sides, until the Italians seemed a being that grew with death and for that reason was incapable of dying, and all we could do was follow our own who had survived and retreat down the steep back of Santo, so that by evening it was in enemy hands.