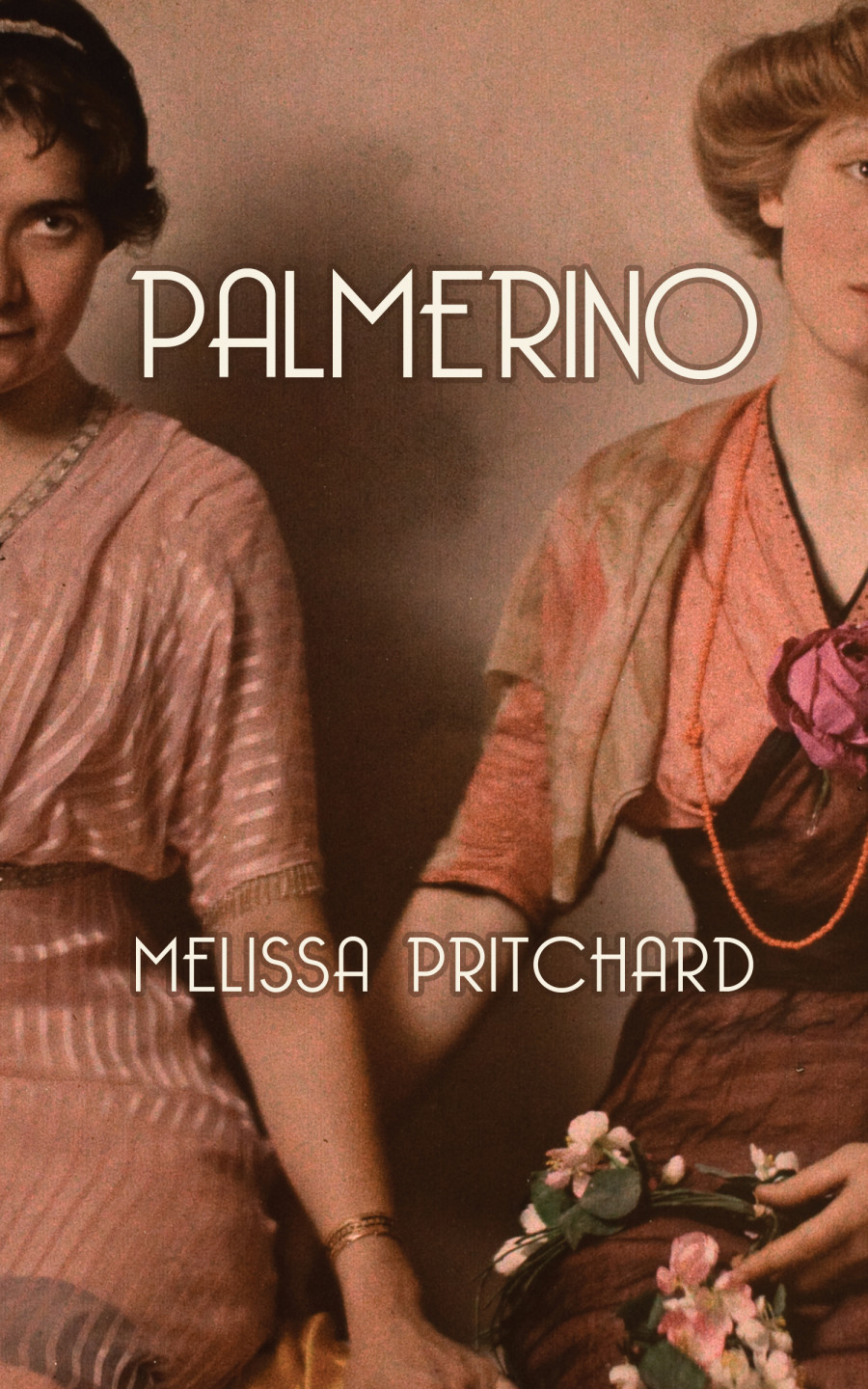

“A richly imagined, sensuous tale of a British writer holding court in Italy, flouting Victorian mores via her writing and her sexuality.”

O, The Oprah Magazine

-

on

“Slim and poetic . . . the mood is of thunderstorm air thick with loneliness and longing.”

National Post

( link)-

on

“Part love story (or stories), part treatise on aesthetics, part mysterious tale of the supernatural, Palmerino [is] a tale of multiple seductions.”

Phoenix New Times

( link)-

on

“A novel of allure . . . as fanciful as Astrid Lindgren’s Villa Villakula and foreboding as The Eagles’ “Hotel California,” Palmerino is surprising at every turn, sometimes frightening, and above all beautiful.”

Lambda Literary

( link)-

on

“Melissa Pritchard has opened the door to understanding a once famous British lesbian writer. . . . Palmerino is a beautifully written and well-structured work.”

Gay & Lesbian Review

( link)-

on

“[Palmerino] draws its life from its large and vivid characters. . . . With her signature hothouse lyricism and psychological acuity, Pritchard carries us fully into her created world.”

Image: Art, Faith, Mystery

( link)-

on

“In a mere 192 pages, Melissa Pritchard has created a rich, lush, and riveting story of two women writers in different eras.”

Shelf Unbound

( link)-

on

“The achingly gorgeous prose in which Palmerino is written strikes pitch-perfect harmony with its equally strong expression of humanity, promising that the hidden beauty within is always worth the time it takes to discover it.”

CCLaP: Chicago Center for Literature and Photography

( link)-

on

“A fascinating historical novel. . . . A mesmerizing love story. . . . Magnificent.”

Connotation Press

( link)-

on

“Fiction can reimagine flesh-and-blood folks to stunning effect . . . What a pleasure, then, to discover Melissa Pritchard’s Palmerino, which envisions the life of Vernon Lee, the pen name and male persona of Englishwoman Violet Paget. Opening with the contemporary story of Sylvia, who discovers Lee while working at Villa il Palmerino in the Italian countryside and becomes her biographer, this work is related in sun-on-raindrops prose that draws in readers.”

Barbara Hoffert, Library Journal Book Expo America Editor’s Pick

( link)-

on

“Enthralling . . . An intriguing introduction to Violet Paget, and an unusual look into the mysteries of writing.”

Booklist

( link)-

on

“A supernaturally infused, innovative story . . . Pritchard’s fertile imagination and presentation give new meaning to the expression ‘a meeting of the minds.’”

Kirkus Reviews

( link)-

on

“Lush, tactile descriptions and impressionistic scenes bring alive this historical novel . . . cast[ing] Paget and her late nineteenth-century lifestyle in a captivating light.”

ForeWord Reviews

( link)-

on

“Rarely has a novel based on real people reached such deftly crafted literary excellence as this historical work of fiction clearly documenting Melissa Pritchard as a writer equal to any of the people populating her superbly presented story. Palmerino is a complex and entertaining novel that is highly recommended for personal reading lists and community library literary fiction collections.”

Midwest Book Review

( link)-

on

“Pritchard skillfully blends the past and present in her novel Palmerino, a book both richly lyrical and highly imaginative.”

Largehearted Boy

( link)-

on

“A fascinating, unexpected way to enter into Vernon Lee’s life. Highly recommended.”

Rosemary & Reading Glasses

( link)-

on

“Dazzling in its descriptions, lush and lyrical in language, Palmerino is a jewel of a novel. It is a tale to be savored like a rich Italian pastry. Melissa Pritchard’s characters—eccentric, quirky, and brilliant—will live on in the heart and mind long after the last crumb is licked from the plate.”

Naomi Benaron, author of Running the Rift

-

on

“At the heart of Palmerino lies beauty, grace, longing, love. Melissa Pritchard’s picturesque prose is fertile, sensuous, a voice of insight, truth. Unique and refreshing as ‘the great female soul that is Palmerino.’ Gorgeous and heartbreaking. This book is a sensual treasure.”

Kim Chinquee, author of Pretty

-

on

“Palmerino finds Melissa Pritchard’s signature style in peak form. Pritchard is a writer of sensibility. Her unique gift is the ability to interweave the resonances of consciousness—memory, intelligence, emotion—with those of a historical time and a powerful sense of place, so that character emerges as a coherent, credible, internal voice uttering a sensual flow of language, both lush and precise.”

Stuart Dybek, author of The Coast of Chicago

-

on

“This lovely, sexy novel provides a sumptuous glance into the secret lives of artists. At its center is Violet, a fierce woman who never met a rule she didn’t break. Melissa Pritchard’s voice is completely her own and her characters are as unique, wild and magical as she is.”

Tayari Jones, author of Silver Sparrow

-

on

“Bounding between Italy today and of a century ago, a breathtaking gallop through intellectualism, feminism, sexuality, cultural history, honeysuckle, focaccia, plums, language, landscape, love, the supernatural, metafiction, mortality and resurrection, with Pritchard always firmly at the reins.”

Anne Korkeakivi, author of An Unexpected Guest

-

on

“A taut and elegant imagining of Vernon Lee’s life that sparkles with Einfühlung for the writer, for Italy and for the love—wild, unconsummated, shattered—that lies at the heart of the best creative work. Weaving fact and fiction, past and present, Palmerino becomes its own beautiful mirror, a work that ‘slips free of the self’ to reveal the mysterious other. Sublime and moving, its gorgeous prose haunts the reader long after the last page.”

Ana Menéndez, author of Adios, Happy Homeland!

-

on

“Seduction is at the lush heart of Palmerino. The Florentine retreat seduces us just as surely as it seduces the lonely and abandoned Sylvia, an historical novelist who in turn is seduced by the spirit of the brilliant Violet Paget, who lived there a century earlier. Writing as Vernon Lee, Violet’s own seduction is one of the most quietly erotic scenes ever written.”

Pamela Painter, author of Wouldn’t You Like to Know

-

on

“In her subtle yet breathtaking new novel, Palmerino, Melissa Pritchard seduces us once again with her characteristically sensual and deeply poetic prose. Elegantly braiding time, this woven narrative is calibrated by Pritchard’s exquisite erotic reckonings and resonant aesthetic reflections. In resurrecting Violet Paget/ Vernon Lee at our own historical moment (and by invoking a gallery of beloved and provocative artists and esthetes), Melissa Pritchard has provided for her readers a portrait-mirror in which to gaze—a glorious vision of both Palmerino and of a writer in pursuit of its history—one that would make even Oscar Wilde blush with envy.”

David St. John, author of The Auroras

-

on

“Melissa Pritchard stands out among contemporary writers for her ability to portray the complex inner lives of her characters. As we follow them through their experiences and memories into their dreams, we’re invited to flex our own imaginations, even, if we’re willing, to become more supple thinkers, thanks to this writer’s supple prose.”

Joanna Scott, author of Follow Me

-

on

“A brilliant novel whose cast of characters, strong, strange, vivid, eccentric, will make you feel enriched and enlivened, and will leave you wanting to visit, or to visit again, the rich interiors of Tuscany past and present, the opulent mysteries of its food and wine, and not least the magic of its natural landscapes and seasons. Melissa Pritchard’s delicate and precise prose achieves all this, as if casually, while capturing her reader in the forward momentum of her story.”

C.K. Stead, author of Mansfield

-

on

Is not empathy that consciousness leading us, unwitting, into the realm of spirits, avatars, even demons? Are not the dead still trying to reach the living?

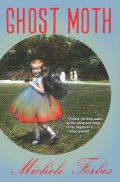

Welcome to Palmerino, the British enclave in rural Italy where Violet Paget, known to the world by her pen name and male persona, Vernon Lee, held court. In imagining the real life of this brilliant, lesbian polymath known for her chilling supernatural stories, Pritchard creates a multilayered tale in which the dead writer inhabits the heart and mind of her lonely, modern-day biographer.

Positing the art of biography as an act of resurrection and possession, this novel brings to life a vividly detailed, subtly erotic tale about secret loves and the fascinating artists and intellectuals—Oscar Wilde, John Singer Sargent, Henry James, Robert Browning, Bernard Berenson—who challenged and inspired each other during an age of repression.

O, The Oprah Magazine “Title to Pick Up Now”

Chicago Tribune/Printers Row Journal featured excerpt

GayRVA.com “Top 5 Summer Read”

Society Nineteen “Fiction Favorite”

Publishers Weekly “Big Indie Book,” Book Expo America “Galley to Grab,” and Book Expo America “Big Book of the Show”

Library Journal Book Expo America Editor’s Pick

American Library Association “Over the Rainbow List” selection

Excerpt from Palmerino

With a faint rustle of her maroon-and-black-striped faille skirt, Mary Robinson trails her parents up a cool staircase leading to the Pagets’ lodgings on via Solferino. Glad to escape the unseasonal heat of an October afternoon, she is eager to make the acquaintance of the Pagets, rumored to be an intellectually rigorous, if peculiar, family. At the insistence of a friend who had recommended them, Mr. and Mrs. Robinson have accepted an invitation to tea at the Paget residence before returning to London. They have just come from Venice, where Mary was introduced to Henry Layard, an archaeologist whose discoveries at Nineveh had so fascinated her at the British Museum, as well as to Ernest Renan, the heretical French philosopher, theologian, and Orientalist. Mary has just published her first volume of poetry, A Handful of Honeysuckle, and with her innate confidence further bolstered by adoring parents, she has assumed a tenuous place on the lower rung of London’s literary circles.

In response to Mr. Robinson’s firm knock, a female servant draws open the massive black door to the Paget residence. Mary follows her parents into an imposing north-lit room with ornate embossed ceilings, a series of high, narrow windows swagged with crimson satin brocade, and a purplish marble mosaic floor. Yellow roses bloom from various antique painted pots, and a quantity of dark, carved eighteenth-century furniture is placed, with no apparent plan, about the room—including a priest’s confessional box, uncurtained and piled with firewood. In the midst of this shadowy, storybook atmosphere sits a slight young woman with golden brown wavy hair, her inquisitive gray eyes strangely magnified by a fantastic pair of huge eighteenth-century green goggles. Violet Paget stands, stretches out a hand, the slim white fingers emerging like petals from the cutting immobility of her black dress’s severe cuff, and greets each of her guests by turn. (For her part, Violet is struck by the young creature rippling toward her, holding a dainty lace-edged parasol. The otherworldly luminosity, the charismatic dark eyes limpid with sympathy—exactly how she has always pictured the baron’s clever daughter in Scheffel’s Der Trompeter von Säkkingen!)

The first hour passes in glittering arpeggios of polite conversation accompanied by cups of black tea and milk, followed in the second hour by biscotti and glasses of vin santo. From his horizontal pulpit, Eugene tells in a delicate, oratorical whisper, more breath than sound, the latest tattle on his little sister, Violet. Just yesterday, he whispers, she had crouched in the garden shrubbery beneath an open window while their mother, sitting at her piano near that same window, tinkled out the crystalline opening notes of an eighteenth-century song, “Pallido il sole,” Hasse’s piece, famously sung by the castrato Farinelli to mad King Philip of Spain—music that had arrived by post that morning. Unwrapping the paper parcel from Bologna, Violet declared that her reputation hung on this one composition, and had handed the score to mother before hurtling downstairs into the garden to hear each note as it floated through the window, released from ivory and black keys by the imperious, agile pressure of Matilda’s fingers. Moments later, Violet crept upstairs to further listen through the cool plaster wall of an adjoining room, against which first her left, then her right ear pressed flat. Hasse’s song proved superb, thus preserving the theories she had set forth in Studies of the Eighteenth Century in Italy, published earlier that year by W. Satchell and Co., London.

Mary Robinson listens to Eugene whisper on about his sister, thinking what a paradox she seems, this small, strange-looking Violet Paget. All outward timidity and childlike vulnerability, yet bristling, picketed, by a ferocious, encyclopedic, old mind.

The next day, Mr. and Mrs. Robinson acquiesce to Mary’s and Violet’s pleading and leave for London without their daughter. They have agreed to let Mary stay on with the Paget family, though, as they later discuss between themselves on the train, the household is nothing if not bizarre, what with the brother broadcasting from his rolling bed like some hermaphroditic Roman pedant, only the large, slipshod mouth moving, and the tiny mother, embalmed in the resin of eighteenth-century fashion and speech, straight down to her oyster-colored, bobbing ringlets and strange Quaker usage of “thee” and “thou!”—followed by the Byronesque father (what was his name?), mute as stone but for an occasional non sequitur regarding the superior hunting and fishing to be had in a place called Thun, and finally, young Violet, her opinions and recitations erupting lavalike from a brain of seeming universal capacity and in such a stammering, pinched, unfortunate voice that her physical composition, poor child—that great jutting man jaw, porcine eyes and thin suet-colored hair—is only further accentuated. Still, they saw no harm in Mary’s forming an otherwise brilliant acquaintance.

The Robinsons’ afternoon visit had been a mere foretaste of their daughter’s monthlong stay with the Pagets, a sojourn Mary will detail in a barrage of daily letters to her parents. Imagine, she writes, a household existing only to debate opinions of art, music, poetry and philosophy, a family (aside from the father, who is largely absent) breathing only, morning till night, for the disciplined pleasures of the intellect. Mary describes late-morning excursions in a landau specially kitted out for Eugene, a smoothed plank laid across the sides so that he can lie prone upon it, how she and Violet perch on either side, vestal creatures, shading Eugene’s broad, pallid face with black silk parasols while Beppe, with his team of bays, drives them out of Florence, high into the pastoral hills and winding streams of San Gervasio along a dirt road following Lungo l’Affrico, the very stream referenced in Boccaccio’s Decameron! Sometimes she and Violet climb down from the cart to gather armloads of forget-me-nots, reeds, boughs of spindle wood, small bunches of grape hyacinth and wreathe Eugene’s straw hat with loose garlands of wildflowers. In one letter, Mary attempts to convey the atmosphere of the Paget salons, the parade of stellar visitors—the Italians (Carlo Placci, Enrico Nencioni), the Russians (Peter Boutourline), the French (Anatole France!), the Americans and the British (Henry James, Aldous Huxley), the Germans (Karl Hillebrand, Adolf von Hildebrand)—really, she can’t be expected to remember them all—glittering constellations of sculptors, critics, composers, poets, translators, musicians, diplomats, novelists, and always, there comes that last, inescapable salon hour when Matilda Paget, a demiregal doll creature, faded ringlets bouncing, attacks her piano’s keyboard, everyone in the room made to listen to the explosive or subsiding end, of Beethoven, Schubert, or Scarlatti. In one letter to her parents, Mary quotes Eugene, how he had opined during that day’s luncheon, with a sour expulsion of air from his lungs, that “invalidism, like infection, breeds sublime poetry.” The horizon, he labored on, was his singular vantage point. Fastened to his board by day, wheeled about by servants, sideways and aslant, at night, in dreams, he is upright, walking freely. . . . “I speak from the perspective of the dead, though I am as yet unburied. There are twelve types of horizon I have discovered and given name to. . . .” This, Mary writes, is one manner in which Eugene might open a conversation with whoever is near—in this case, herself. His poetry, what she has read of it, is sluggish, black-veined stuff, tragic as drowning. The poems, she confides to her parents, seem overinfluenced by Poe and Baudelaire; several are fatally tinctured with self-pity.

She writes nothing of Eugene’s sister, because she has fallen in love with her. And because in Violet, who has begun to use the pseudonym Vernon Lee (“Let us admit that any male writer shall always receive more attention than a female”), Mary has discovered a friend whose knowledge of music, literature, and art surpasses her own. Has ever such a gorgeous mind issued forth from a mere woman, Mary marvels, writing in her private journal by the thin, sallow light of a bedside candle. Being with Violet is intoxicating, how Mary imagines it must have been to be in the presence of the French Symbolist poet Verlaine. Vernon—she really must stop calling her Violet—expounds easily on any manner of subjects in any of four subtly conjugated languages, French, German, English, and the Tuscan dialect of Dante. The breadth and depth of her friend’s intelligence, enfolded, engraved deep within its young brain, can never be fully sounded; it settles around Mary like a cloak or climate, like some infinite and liberating perspective. And though Mary sometimes hears her friend’s verbal wit descend into cruel impatience, she still admires her. If Vernon cannot abide hypocrisy, must attack and undo it with pitiless words, is there not rough honor in that? Aware her own ideas and opinions are diluted with counterfeit kindness, Mary is inspired, watching Vernon brandish her way through dense thickets of social nicety and dead form.

Their month together passes quickly, and on the morning she must leave, Mary extracts a promise from Vernon that she will visit London the following Spring and stay with Mary in her parents’ home on Gower Street, a mere twenty-minute walk from the marvels and antiquities of the British Museum.