“Rinzler lifts the lowly human foot to new heights in this appealing book.”

Booklist (starred review)

( link)-

on

“An in-depth look at the anatomy and history of feet reveals their often overlooked importance in human evolution, medicine and art.”

Science News

( link)-

on

“Stylish, informative, entertaining, and pleasantly personal . . . Whether Rinzler is exploring how our feet explain or illuminate such topics as evolution, disability, racism, diet, or desire, she maintains a fascinating perspective on the peculiarities of being human.”

Rain Taxi Review of Books

-

on

“Entertaining and wide-ranging. . . . Well researched and clearly presented.”

Literature, Arts and Medicine Database

( link)-

on

“This neat little book draws a clear picture of our feet, providing understanding that extends far beyond the obvious. Readers often like to walk away from a book feeling they learned something—that the author left them with a new way to look at an old idea, and this book fulfills that need.”

City Book Review

( link)-

on

“Carol Ann Rinzler has written a surprising and delightful book about this ‘underwhelming, underreported, and completely indispensable’ part of the human body. It’s amazing what you’ll learn!”

Richard N. Gottfried, Chair, New York State Assembly Health Committee

-

on

“Carol Ann Rinzler weaves together material from art, literature, science, and history to broaden our understanding of the human foot. Her book is by turns entertaining, enlightening, and altogether satisfying.”

Congresswoman Carolyn B. Maloney

-

on

“Among the many pleasures of this book are the intriguing subject, Carol Ann Rinzler’s lively and accessible writing style, and the amazing array of information she has gathered from so many different fields . . . Who knew that the story of our own feet could be so fascinating?”

Sandra Opdycke, author of No One Was Turned Away and Jane Addams and Her Vision for America

-

on

“This book will amaze you as it walks you through evolution, history, mythology, and a good dose of anatomy, to enlighten you about the role of the Humble Human Foot in bringing human beings to where we are today. Thoroughly enjoyable, informative, and well written, it is a must read for anyone involved in caring for our lower extremity—or interested in our evolution. In short, you will never view the foot the same way again.”

Gary Stones, DPM, President, New York State Podiatric Medical Association

-

on

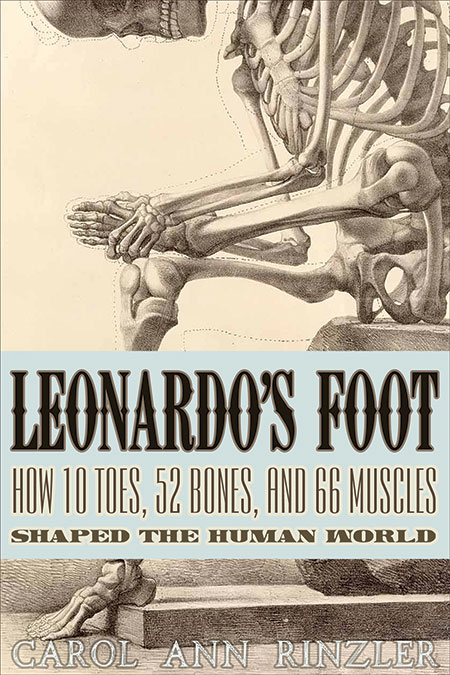

Leonardo’s Foot stretches back to the fossil record and forward to recent discoveries in evolutionary science to demonstrate that it was our feet rather than our brains that first distinguished us from other species within the animal kingdom. Taking inspiration from Leonardo da Vinci’s statement that “the human foot is a masterpiece of engineering and a work of art,” Carol Ann Rinzler leads us on a fascinating stroll through science, medicine, and culture to shed light on the role our feet have played in the evolution of civilization.

Whether discussing the ideal human form in classical antiquity, the impressive depth of the arching soles on the figures in Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, an array of foot maladies and how they have affected luminaries from Lord Byron to Benjamin Franklin, or delving into the history of foot fetishism, Rinzler has created a wonderfully diverse catalogue of details on our lowest extremities. This is popular science writing at its most entertaining—page after page of fascinating facts, based around the playful notion that appreciating this often overlooked part of our body is essential to understanding what it is to be human.

A Selection of the Scientific American, History, and BOMC2 Book Clubs

Excerpt from Leonardo’s Foot

There are 206 bones in the adult human body. When you put down this book, push back your chair, and stand up, you will be standing on 52 of them: Your two feet.

Human beings are bipeds. We naturally and consistently stand and move on two feet rather than four or eight or any other multiple of two.

We share our bipedalism only with birds and two species of mammals, the macropods—“big footed” kangaroos and wallabies—and the very small-footed kangaroo mice, jumping rodents native to the Southwestern United States. As avian anatomists know, birds hop on what looks like two feet but is actually comparable their toes; the “heel” of a bird’s foot is part of a toe; the piece just above that corresponds to the sole of your foot. Theoretically, all the rest of us can walk, run, jump, and jog, although the last—a compromise between walking and running—is pretty much the province of humans.

Each of us owes our two-footed stance to the prehistoric sea creatures who developed fins strong enough to enable them to crawl up the banks of the local watering hole and become land animals; then to Eduibamus, a reptile with long back legs and short front ones, thought to be the first known biped; virtually all dinosaurs, some crocodiles, and every bird on earth that stood up on two legs and started to move by putting one foot in front of the other; and finally to a confluence of geography, climate, and biological selection which produced the foot on which we stand today.

Leonardo da Vinci, no slouch himself at anatomical mechanics, described this foot as “a masterpiece of engineering and a work of art.” His famous drawing, “The Vitruvian Man,” lays out the standards for the ideal human male figure from head to, yes, toes attached to a foot which, ideally, should measure one-sixth the height of the body.

It is possible that Leonardo saw something of himself in the ideal man. In Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550), Giorgio Vasari described da Vinci as “an artist of outstanding physical beauty” and a man endowed by heaven with beauty, grace and talent.” Dutch portraitist Siegfried Woldhek has suggested that Leonardo may have used his own features as the model for the Vitruvian man. Certainly he was not shy about his physical appearance; even as the older man portrayed in the statue that stand outside the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, he preferred to show his legs, wearing clothes usually reserved for younger men.

Over the centuries since Vitruvius wrote his rules and da Vinci made them immortal, the marvelous human foot has walked its way straight into the English language:

Sometimes, we mistakenly set off on the wrong foot when, to be successful, we should put our best foot forward and start off on the right foot, a trio of locutions that track back to the ancient relationship between left (sinistre) being wrong and right (dextra) being, well, right. And if you have noticed that many of the people in Egyptian paintings seem to have their feet on wrong, you’re right. In Egyptian art, only the royals had both a right foot and a left foot; lesser mortals were drawn with two left feet.

Today, timid people have cold feet, the imperfect have feet of clay. The decisive will put their foot down, the bold jump in with both feet and, regardless of the fall, always land on their feet. Those in a hurry hot foot it along. And if any of these fail to give us a proper answer to a proper question, we will hold their feet to the fire.

At The End, most of us leave this world feet first so that our spirits will not be tempted to return—unless the feet in question are attached to the body of a priest who is carried from the church head first, looking back at his congregation to which he expects to return.

At least in spirit.